70 Hiroshi Naito(Architect)

While teaching at the graduate school of the University of Tokyo from 2001 to 2011, architect Hiroshi Naito designed numerous buildings such as the Sea-Folk Museum and Makino Memorial Museum. In this interview we learnt something unexpected about the fabled record shop Roppongi Wave. Naito helped to organize the "DOBOKU Civil Engineering" exhibition being held at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT and we started the interview by asking about the exhibition.

The good people in civil engineering

When I started teaching civil engineering at university, I was surprised to discover that the civil engineering industry is filled with good people. I might be told off for saying this, but we architects are concerned mostly about ourselves. We are interested in who won which award or which competition, but in the world of civil engineering, hardly anyone talks about such things.

The civil engineering people are constantly thinking about how they can protect people from natural disasters like the 3/11 earthquake, and how they can use engineering technology to improve the lives of people. In their minds, the public comes first, and matters of the individual come last. It's such a marvelous mentality. They know everything about the positive and negative aspects of nature; they have a pure love for nature and they are so interested in it. For example, the civil engineering people doing work on rivers are always thinking about how they can restore the waters to their natural state. Professor Masahiko Isobe, who is an expert on coastal engineering, boasts that he has gone swimming on all the shores of Japan. (laughs)

Working in the field of architecture, I've always felt somewhat uncertain about the importance placed on the sensibilities and works of individual architects. So I was spiritually saved when I encountered the values held in the world of civil engineering, Nonetheless, I still have to work as an architect, so there is a contradiction there.

"DOBOKU: Civil Engineering" Exhibition

An exhibition that looks at the design aspect of civil engineering. Items on display include drawings of dismantled interiors of stations, images of civil engineering projects accompanied by actual sounds recorded at construction sites, as well as plastic replicas of curry and rice dishes shaped like dams. The exhibition will be held until Sept. 25 (Sun) at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT.

http://www.2121designsight.jp/

Widely-held misconceptions about civil engineering

There is a well-known joke at the University of Tokyo where I used to teach. A graduate of the University of Tokyo with a degree in civil engineering is considered to be a super-elite. When he joins a construction company, he undergoes training and goes to the construction sites of subway stations and roads. When he pops his head up through a manhole, a young mother passing by tells her child, "If you don't study hard, you will end up like that man." (laughs)

The joke reflects misconceptions held about civil engineering. It also reflects the notion that a person with good grades and a university degree is of higher rank, which is an outdated idea. I think Hiroshi Nishimura-san, the exhibition director of the "DOBOKU Civil Engineering" exhibition, wanted to protest against such widely-held misconceptions.

Japan's failure to change after 3/11

I didn't realize this when I was working solely in the field of architecture, but civil engineering - from railroads to roads, rivers, ports and airports - is the true driving force of this country. I'm currently involved in a redevelopment project in Nagoya which consists of building a maglev line for the "shinkansen" bullet trains; apart from the driving-related technology such as motors and vehicles, almost all the technology being used is related to civil engineering such as building railroads and digging tunnels.

In the future, it will take only 40 minutes to get from Shinagawa to Nagoya. If you went drinking with a friend and parted at Shinagawa, your friend would arrive home at Nagoya while you are still drunk and making a full circle on the Yamanote Line. That will happen in ten years' time which is not far off at all.

I've talked about the good aspects of civil engineering, but there are also some things that we were unable to change for the better, and I feel bitter about that. When the 3/11 disaster occurred, I personally thought it would prompt change in Japan. But it didn't. The administrative system for reconstruction started moving in the way it has always moved. Only the familiar-looking tools on the table were used to deal with the problems. My efforts to stop it were in vain.

The big picture and the practical steps

I talked about this in the movie for the DOBOKU exhibition, but in the aftermath of that earthquake, we had to get two things right. First, we needed a clear vision of a better life for the people who were affected by the disaster. Second, we needed to take the practical steps like setting up seawalls, rezoning land, and making roads.

Of course, there were many practical steps that had to be taken. But no one knew whether these steps were actually helping to realize the vision. The people in administration and the people making the roads were working so hard that you felt for sorry them, but somewhere in their hearts, they had doubts about what they were doing.

Ideally, everyone should have kept their eyes on the big picture while at the same time flexibly adjusting the steps they were taking. But in reality, they were not able to do that because no one had gone through such an experience before. The problem lies not with individuals, but with the social system of Japan as a whole. The social system and the subsidy system and the legal system were all set up in the 1960s...

A big disaster that would change our way of thinking

After World War II, everyone wanted abundance, and they had a clear goal of getting the economy back on track. That was the goal for about 50 years, but now, if you ask people what kind of future they want, they probably won't be able to give a quick and precise answer.

Unless there is a huge disaster like a direct-hit earthquake in the city, or a movement of the Nankai Trough, the Japanese are not going to change the way they think. I hope you don't mind me talking about something a bit complicated, but during the 3/11 Great East Japan earthquake, the number of people who died or went missing came to 20,000. If a Nankai Trough earthquake occurs, 300,000 to 360,000 people are predicted to die; the scale of damage would be roughly 15 times bigger. Since the reconstruction budget for 3/11 is 24 trillion yen, the reconstruction budget for a Nankai Trough earthquake - calculated simply - would be 360 trillion yen. However, the government will not be able to spend such a large sum, and we will inevitably have to think of another system.

Since the government won't be able to do everything, communities will need to get together and come up with ideas. We will have to think about what kind of families, communities, architecture, cities and designs we want. Our way of thinking will change, although I can't tell how. I myself wish to keep thinking about these matters. I hope that things will change in a good way.

An exhibition that provides hints for the future

There's a lyric in one of Linda Yamamoto's songs that goes, "You mustn't believe rumors". Nowadays, people look at television and magazines and SNS, and think they know it all. But to grasp the real information with your bare hands, you need to delve deep to a certain level. In my case, I dug deep in the genre of architecture and I was able to understand the connections to civil engineering and city development and even to physics and design; once you have an area of expertise, you can see how everything is connected.

The DOBOKU exhibition shows how the future of civil engineering and the future of architecture and the future of Japan are all connected. The exhibition provides hints for the future that will come after the world has changed. It shows all kinds of elements, ranging from the actual things that are made by the workmen to the latest technology such as Rhizomatiks' sensor-based installation and a sandbox using three-dimensional design technology.

What we have to do next is to consider how to use these elements to make new things. We don't want to make the exhibition too difficult though, because that would turn visitors away; we want people to come and have an enjoyable experience and perhaps later, there might be moments when they will recall what they have seen and think, Oh, I get it.

Among the items shown is "Doboku no koi tameru (Civil engineering step - monitoring): Perfume Music Player Installation" by Rhizomatiks. Using the location information from smart phone applications, the installation shows the transportation network in Tokyo and the movements of phone users.

Photo by Keizo Kioku

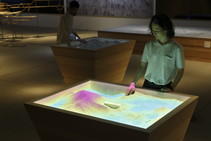

A visual installation called "Doboku de asobu; daidara no sunabako (Fun with civil engineering; daidara sandbox) allows visitors to play with sand and experience the viewpoint of a civil engineering designer. (Photo by Takashi Kiriyama and Toshiyuki Kuwabara)

The main interview photos for this interview were taken in front of the experience-oriented installation "Doboku no koi tameru(Civil engineering step - accumulating)" by Yakul. The installation shows imagery replicating the dynamic flow of water being accumulated in a dam.

Photo by Keizo Kioku

Giving the name "WAVE" to the record store

I've talked about things that have nothing to do with Roppongi; I happen to be qualified to talk about Roppongi because during the early '80s, I helped set up Roppongi WAVE. When WAVE was to be built, the Seibu Group launched a preparatory committee, and I joined as its youngest member; the committee members included Shigeru Uchida-san and we held many discussions on Roppongi. Then WAVE was built, and the area of Roppongi began to change structurally. So I'm a person who knows its history. (laughs)

In those days, there were many foreigners at the Roppongi Intersection; the neon signs glowed and the streets were garish. I remember Seiji Tsutsumi-san saying, "When everyone is being noisy, you can stand out by being silent." That's why the WAVE building hardly had a signboard. And in an attempt to break the conventions of retail stores, we had wood plank floors. A lot of experimental steps were taken. For example, the artist Katsuhiro Yamaguchi-san created a stereoscopic image of a "holonic jizo" to serve as a protecting deity for the back street of WAVE. All this took place more than 30 years ago.

Incidentally, I'm the one who thought of the name "WAVE". I proposed it because there was the popular "new wave" movement at the time and also because the word suggested music. The name was rejected at some board meeting or other, but it was adopted when the time came to make the logo; the designer Kuni Kizawa-san liked it, saying that if the two letters in the middle of WAVE were shown in different colors, it would look as if "AV (audio visual)" was enveloped in the word "We."

Roppongi WAVE

A record store that opened in 1983. It played a role of transmitting information not only on music, but also on culture and trends. Due to redevelopment in Roppongi, the store was closed in 1999 to the disappointment of many longtime patrons. Roppongi Hills Metro Hut now stands in its former site.

Cities are the reflection of the people

When asked about my favorite city, I often reply Barcelona as it used to be until the early 1990s. I say "until the early 1990s" because it was then that the streets were made clean for the Olympics. Along La Rambla main street, there is the Barrio Gótico or Gothic Quarter, and on the other side is the Barrio Chino, which used to be known as the biggest red-light district in the Mediterranean. Filled with shady people, it was a place where you would not dare walk alone.

That was the dark side of the city, but it gave the streets of Barcelona a distinctive power. Cities reflect people - they mirror the thoughts and desires of people. Just as people have their "omote (public)" side and "ura (private)" side, cities have their two sides. People who don't have their hidden side are somewhat uninteresting, don't you think? But when city development and redevelopment projects take place, those parts disappear.

Roppongi has become an area of redevelopment

A similar thing happened in Roppongi. They built Roppongi Hills, the National Art Center and Tokyo Midtown, and it became a totally brightened-up area. Sad to say, Roppongi is now an area of redevelopment.

Until a little while ago, Roppongi was a more powerful, deep kind of place. There was the TV Asahi building, and you would see celebrities; the backstreets were dark and fishy, and the area around the Roppongi intersection was the place transmitting Japanese culture. Compared to Shibuya which is a valley and where the subculture of the young people is born, Roppongi, which is a plateau, has a deep, high-brow culture.

These deep cultures are made naturally; they cannot be made according to plan. But big development projects are essentially games of investment and return, and they are not compatible with things that grow by coincidence. When a large-scale development takes place, a culture - especially one that hints of the future - becomes difficult to grow.

Standing at the crossroads

Of course, one cannot say that all large-scale developments are bad, but we have come to a point where we need to look at their history and decide where we want to go next. Is Roppongi going to end up as just one huge development project, or will there be an expansion of interesting streets around it, and are people frequently going to get the urge to visit Roppongi? We are now standing at the crossroads.

We need to get together at meetings such as these Roppongi Future Talks and think about what kind of area we want Roppongi to become.

The circumstances in Shibuya - which is an area I've long been involved with - are similar to those in Roppongi. There is now a plan to support the street culture of Shibuya. There used to be small theatre called "Shibuya Jan Jan". Compared to the large commercial facilities, it was a tiny space that had almost no real estate value, but it had a really strong cultural influence. We're currently holding talks, wondering if we could create a place like Shibuya Jan Jan.

Big development projects are easier than smaller ones

Shibuya has its street culture, but what does Roppongi have? Small grains. We already have the big grains and many more large-scale developments are scheduled for the future. This may not be a nice thing to say, but anyone can do big developments. Of course, it's hard work to negotiate with the landowners, but once you have done that, you just count the money for each floor and start building. It's far more difficult to undertake small to medium-sized developments.

I've long proposed to set a rule that whenever a high-rise building like Tokyo Midtown is built, an interesting place is built a little farther away, without giving any thought to its profitability. It can be a small place as tiny as this green pea on this plate of pasta that I'm eating now. I believe investment in such things - which don't require a big sum of money - should be made whenever big developments are made.

Creating a space without a thought to making profit

Perhaps it could be a music venue or an art gallery. It would be a cultural place that is always innovative and edgy, attracting the younger generation. The young men and women who visit the huge commercial complexes would wander off to these places. In such areas, restaurants will pop up because people will need to eat after they've been to an event; IT companies might choose to transfer their offices to these areas, rather than being in a high-rise building. That is the natural way for towns to grow.

Personally, I think what makes Roppongi interesting are the kind of backstreets that a girl wouldn't like to walk along by herself. But the administrative people cannot say they want streets like that and in any case, it would be impossible to intentionally make them. So the best thing is to turn a blind eye to such streets and refrain from removing them as much as possible. What Roppongi needs now are many such backstreets and a lot of "green peas."

You asked me about ideas for the future of Roppongi from the perspective of civil engineering. I hope what I talked about is the kind of thing you had in mind. (laughs)

Editor's thoughts

Many of the creators we have interviewed have mentioned Roppongi WAVE, but we did not expect to meet the person who gave the store its name. The press preview for the DOBOKU Exhibition was held on the same day that we interviewed Naito-san, and since he was busy with this event, we interviewed him over lunch. A blog report on the DOBOKU Exhibition can be read on the site below. (Japanese version only)

(edit_kentaro inoue)