INTERVIEW

92

Sohei NishinoPhotographer

Exhibiting photos in public spaces to delight the pedestrians in Roppongi

Roppongi would be an ideal venue for an outdoor photography festival

The numerous photographs that Sohei Nishino has taken on his travels around the world are visual journals of his personal perspectives and experiences. By putting together the photographs he has taken in a certain city, Nishino makes a single piece of artwork which he calls a "Diorama Map". So far he has made 20 such Diorama Maps. In this interview, Nishino, who has seen the streets, people and lifestyles of so many cities around the world, talked about the fun he had walking in Roppongi and the kind of art he would like to create here.

Roppongi is like a miniature version of Tokyo

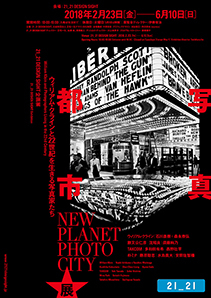

I'm currently participating in the "NEW PLANET PHOTO CITY - William Klein and Photographers Living in the 22nd Century -" exhibition at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT. A while ago, when my works were being shown at a Roppongi gallery, I came to Roppongi regularly for about a month, so I feel a personal attachment to this place. Also, to make a work themed on Tokyo, I walked around Roppongi quite a lot. The concept of the Diorama Map being shown at the "NEW PLANET PHOTO CITY " exhibition is to show my wanderings in a city on a single map. All the things I felt and experienced are expressed on one map; the longer I stay in a place, the more photos I take. When I look at the map I made of Tokyo, I see that I took more photos of Roppongi than I expected. The photos show that I spent a long time in Roppongi, that I did a lot of walking here. I walked about a lot because I found the place interesting.

"NEW PLANET PHOTO CITY - William Klein and Photographers Living in the 22nd Century -" exhibition

An exhibition showing the works of William Klein and other photographers. Klein has greatly influenced contemporary visual culture with his images of cities around the world, and also with his works in genres such as movies and design. A multi-projection was made of Klein's stunning photographs of cities. The exhibition also introduced innovative works by Japanese and other Asian photographers which depict present-day cities and people.

Date: Feb.23 to June 10, 2018

Venue: 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT Gallery 1 & 2

http://www.2121designsight.jp/

"Diorama Map" series

Sohei Nishino's representative series of works based on photographs of cities around the world. Nishino stays in the city like a local and takes images from many perspectives. Once back in his studio in Shizuoka, Nishino develops the film photos. Cutting and assembling the photos in a collage, he recalls his memories and creates a single Diorama Map that expresses his experiences of living in a certain city.

Before I started walking around Roppongi, I had a strong image of Roppongi as being a dark and garish place, which is probably the image many people have of this area. I think that visitors to Roppongi come with the hope of finding a piece of Tokyo that doesn't have the mundane, everyday feel. But when I actually started walking, I discovered that it wasn't like that. The thing that struck me most was that there were many layers to Roppongi - many stark contrasts.

For example, there are intriguing places both in the tall buildings and in the underground, and there is the contrast between the daytime face and nighttime face of the streets. The main streets are garish, but when you walk in the backstreets, you come across quiet spots like shrines and temples, and art museums. You find all kinds of restaurants and cafés, and places where you can get a glimpse of people's everyday lives - places which have a downtown atmosphere. Roppongi is just one area in Tokyo and yet it's like a miniature version of Tokyo itself. Every element seems to be condensed into Roppongi; I don't think there are many places like it.

Learning about a town by getting lost

I actively walk the alleyways in order to make artwork, and I think that getting lost is an important part of the process. I don't carry a map. I just wander about as I please until I get the sense of having melted into the city. When I have reached that stage, my mind is empty, and I am able to move intuitively without having to think "I'll turn right on the next road," or "I'll go left." People often ask me whether I already have a pre-conceived image in my mind of what kind of photos I want to take, but I have absolutely no plans. I just go in the direction of the "sounds", as it were.

When I stroll in accordance with my instincts, I sometimes find myself in small alleyways and get lost. (laughs) But getting lost helps me to learn about the place. And in any case, alleyways are simply fascinating, aren't they? You can hear the voices of people, and there are flower pots under the eaves and curtains of the windows fluttering in the breeze... I love looking at things like that. The colors and sounds and the people you meet differ from town to town - the volume of the sounds differ too. In Tokyo, especially, the colors in the streets are very different according to which area you are in. Roppongi in particular, is a place with different cultures and people. I feel that it's in the alleyways that the spirit of an area is reflected.

I've made two works themed on Tokyo: one is "Tokyo 2004" made in the year 2004 and the other is "Tokyo 2014" made 10 years later. When I made "Tokyo 2004", I lived in Osaka, and I frequently visited Tokyo to take photos. I would stay a week and shoot, return to Osaka and stay there for a week, and come back to Tokyo again. I think I repeated that three times. I seem to have looked at Tokyo through the eyes of a biased tourist and the work of 2004 contains many photos taken in the western part of the 23 wards. There are not many photos of the area around the Sumida River. In contrast, I made "Tokyo 2014" when I was living in Tokyo, and the photos seem to reflect that: there are more images of water and of parks which seem to express my feelings as a Tokyo resident. In the span of 10 years, there were physical changes to the city such as construction of new buildings like the TOKYO SKYTREE®, but there was also a change in the way I look at Tokyo. I'm hoping to take photos again in 2024. I don't live in Tokyo now and I'm looking forward to discovering how I will perceive the city after being away for a long time.

Tokyo 2004" (Above)

Diorama Maps of Tokyo made in 2004, and a decade later in 2014. Walking through the streets of Tokyo, Nishino photographed the people and the city and created the works to document his moment-to-moment experience. "Tokyo 2014" was shown at the "NEW PLANET PHOTO CITY - William Klein and Photographers Living in the 22nd Century -" exhibition.

Tokyo 2014" (Below)

If I were to take photos of Roppongi now in 2018, I think I would walk about the streets for about a month. As I mentioned earlier, Roppongi has interesting layers and contrasts: it offers perspectives from high places and it also lets you experience the sense of delving deep down... I would probably shoot intuitively, taking photos of what I see and when I feel something. I think photographers have a strong instinct to capture whatever is in front of their eyes. It would be fun to take photos of Roppongi again a decade later; I would go back to the route I walked in 2018 and shoot whatever happens to be in front of me.

The unique stillness in the center of Tokyo

Including those of Tokyo, I've so far made Diorama Maps of cities in 20 countries. When I go abroad, I rent an apartment for a month or a month and a half, and I try to acclimatize myself to the neighborhood. The first thing I do is to get a haircut. I call this my "barber project." (laughs) I go to the local barber and have my hair cut to become one of the locals. In Amsterdam for example, I would just say, "Please give me an Amsterdam haircut" and then entrust myself to the barber.

In India, I had my hair cut by a barber doing business in the streets. I got a sort of techno-cut: my hair looked like toasted seaweed with the sides cut in sharp angles. (laughs) When he finished, the barber handed me a mirror; he looked proud as if he were saying, "it's nice, isn't it?" I couldn't help laughing when I looked in the mirror but his boldness was refreshing. In Tokyo's Asakusa, the barber shaved my hair and my eyebrows, and gave me a side-parted hairstyle like that of an "enka" singer in the old days. By first having my hair cut, I get the sense of becoming a local, and I feel that I begin to see things in a slightly different way.

After the barber project, I start walking the streets. I walk around for the first two or three days without a camera, searching for the center of the town - not the geographical center, but a place around which the town revolves. For example, in London it is the River Thames, and in Johannesburg, it is the Ponte Tower; I go to the place from which the city extends outwards.

In my mind, the center of Tokyo is the Imperial Palace. On the map of Tokyo's 23 wards, the palace is also at the center. It's interesting that there is stillness in the middle of the city. I think the Imperial Palace is a very sacred place - new buildings cannot be constructed there and big noises cannot be made. Tokyo is the only city I know which has stillness at its center. Tokyo is looped in with the other big cities of the world, but I think it's a bit different from the others. By searching the center of cities and finding the point around which people's lives revolve, I am able to see the differences between cities.

Photos of the city that seem to clash and yet be in harmony

A total of 11 of my works, big and small, are being shown at the "NEW PLANET PHOTO CITY - William Klein and Photographers Living in the 22nd Century -" exhibition, and I think visitors will be able to see the differences between the cities. I've done group exhibitions before, but the display method at this exhibition is engaging. While photos are usually put up on walls, the photos at this exhibition are placed on boxes that are parallel to the floor, and some are hung midair, and there is also music that blends in with the photos. The works of the different artists give off an energy that seem to clash with each other and yet sometimes seem to interact and merge... It's as if the works disagree with each other in some ways, and yet are in perfect harmony in other ways. That ambivalence - seeming to be right and yet not quite right is what I sense when seeing this collection of works themed on cities.

I think the way a photographer shoots a city is influenced by the person's memories and experiences. Looking at the exhibition, I strongly felt that it is the different interpretations that can lead to a good chemical reaction. Visitors will have their own perspectives, and I think they will be compelled to look all over the place. That would be an unusual experience to have at a photo exhibition; it would be kind of similar to standing in the middle of the city. I hope lots of people come and have that experience.

Drawing the line between a traveler and a resident

When I go abroad to make artwork, I walk all over the streets for the first two or three days, and then I interact with the local people and go to all kinds of different places. People tell me about the interesting spots, so I make up a rough plan to go a certain area on one way, and to another the next day. That's how it unfolds. The Diorama Map is not an accurate map, but my aim is to create a map-like work as a form of artistic output. To do that, I need to walk everywhere.

As I said earlier, I rent an apartment for a month or a month and a half and try to blend in with the everyday lives of the local people, but of course, it's not possible to become a true resident. There's a certain period during which I can maintain an awareness of where I am, and that's a factor that determines how long I stay. When I stay more than two months in a place, I begin to look at things through a local's eyes. That seems to make the photos I take slightly more personal. The longest I can stay in a place as a traveler is a month and a half - that's the feeling I have. Once, there was a time when I stayed abroad for more than a month and a half for something that wasn't related to work; I found that strolling through the streets every day made me know the place too much. Since my aim is to make artwork, and not to become a local, I always set a limit to the length of my stay.

When I return to Japan, I start working at my studio in Shizuoka; as I work, it feels as if I'm still on my trip. My work takes about four or five months to complete, but when I stop halfway, my memories become disconnected. So once I'm back from my trip, I keep working. I use about 200 to 250 rolls of film and developing the photos alone requires effort. (laughs) When I've developed the photos, I print them on a contact sheet and cut them out one by one. Then I paste the photos on a canvas and lastly, I take a photo of the canvas - that's how I make my works.

In these times, it's possible to make the collage digitally and do away with all the time-consuming work. But unless I do the work manually, I cannot preserve my memories. All my memories are in the tens of thousands of photos I take, and to recall those memories, it's vital for me to physically touch the photos. It's important that I feel the texture of the thin film and of the photos as I wet them and dry them in the developing process. Taking the physical approach seems to help my memories come back. The Diorama Map that I end up with is my footprint, and it is also a record of the memories of a city and its people at a certain time, in a certain moment.

Utilizing Roppongi's land features in exhibiting photos

I have participated in a photography festival called "Images" which is held in Vevey, a small town in western Switzerland. The work I made then was "Diorama Map Bern". The photo was printed on tarpaulin and placed in a square near the station. It was displayed so that pedestrians could walk over it. It was a Diorama Map of Bern, which is a city that the local people know well, and the children had fun with the work, saying things like "Oh, this is so-and-so!" and "That's where my friend lives." I myself enjoyed the experience of displaying a work in a public space.

Images Vevey

A biannual photography festival held in Vevey, a town in the western part of Switzerland. Works are shown in public spaces such as stations, churches, schools, cafés, and department stores.

Diorama Map Bern

A Diorama Map of Bern by Nishino which was exhibited at Images Vevey. The images were printed on waterproof, resistant tarpaulin which was 10 meters by 10 meters large. A display board that stood as high as a conference table was created to mount the work.

Diorama Map New York

A work showing the streets of New York in 2006, the year Nishino traveled to New York, five years after his prior trip when the 9/11 terrorist attacks occurred.

The other photographers showed their works in all kinds of ways. One photographer covered the round dome of a police building all over with printed images, while another floated photos on a lake called Lac Léman. There was also a photographer who displayed a photo of a waterfall on the outside wall of a hotel... About 10% of all the works were exhibited inside buildings while 90% were shown outdoors in public spaces. I think displaying photos like that in public spaces would be very suited to Roppongi.

There are many slopes in Roppongi, so perhaps the slopes could be printed with images, or perhaps large photos could be put on the tall buildings standing on top of the slopes so that they are visible from afar. Or perhaps photos of things that you least expect to see in Roppongi could be placed on the roads and lawns; the people walking on the ground will not be able to tell what these things are, but the people in high buildings such as the observatory at Roppongi Hills will be able to clearly see the images - I think that would be fun. It would be good if all kinds of artists from abroad could be invited and if their work could be shown in public spaces all around Roppongi.

A photography workshop for everyone with a camera or smartphone

As I said earlier, Roppongi is a place that is fun to walk around; the more you walk, the more varied the streetscape becomes. That's something I experienced, and I think it would be even more fun if there were photos in the streets to look at - it would give people an additional motive.

If I were to hold a workshop, it might be interesting to have around a hundred people walk around Roppongi for a few hours taking photos, and then we could make a map by putting together all the photos that everyone has taken. That kind of experiment would be possible because everyone is a photographer now; cameras are equipped with cell phones, and so there is hardly anyone who doesn't own a camera.

Having taken photos in Tokyo and cities around the world, I've recently become interested in rivers. Whenever I go to the river, I am very soothed. And when I get lost in the streets, I instinctively search for the river. I've been wondering why, and it occurred to me that people in the past must have looked to the river and figured out where the water came from and where it was leading to. Landscapes may change, but what people feel and imagine do not, and maybe I am comforted by the fact that our subconscious feelings and senses remain the same.

When I walk through a developed city that is filled with many buildings, I ponder about how it was transformed, and I begin to see the reasons for people gathering there - factor such as the convenience of distribution and the pleasant environment. And almost always, I come across a river landscape. The river makes it possible for goods and people and culture to flow in... And I realize that the city I see now is the cumulative result of all the things that happened in the past.

A city I would like to revisit to take photos

Il Po

Nishino's newest work based on his trip to the Po River in Italy. The Diorama Map records the experiences that Nishino had as he followed the river flowing through the Alps to the sea. The work is wide, standing at about 8 meters square.

Those thoughts were on my mind when I made "Il Po" themed on Italy's Po River; I only recently completed the work. The river runs a length of about 650 km through northern Italy from the Alps to the Adriatic Sea. I traveled along the river to take photos, first climbing the mountains to capture images of the trickling water, and then following the river as it became wider and joined the sea. I was able to see for myself the reality of water circulation, and it was a personally meaningful experience.

I've made two Diorama Maps of Tokyo, but so far I haven't made two maps of any other city. I would like to take photos of New York again though. I was in New York when the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001 occurred. I'd visited the World Trade Center the day before. When that landscape disappeared, I wanted to create something, and so I made "Diorama Map New York." I wonder what the scenery is like now and what kind of new buildings are standing there. New York is a city I am fond of, and I would like to take photos of the city again someday.

Editor's thoughts

It was very interesting to learn about Nishino-san's perspectives regarding his work, and about the process he takes in making them. Nishino-san also had many interesting anecdotes to tell us about his travels. After the interview, he amused us by telling us about the time that he tried lamb's brain for the first time at a restaurant in Africa. "It was quite a remarkable dish - it had a fairly strong smell," said Nishino-san laughingly. I am sure that it is Nishino-san's open-mindedness which enables him to blend in with the locals wherever he travels. (text akiko miyaura)

RANKING

ALL

CATEGORY