INTERVIEW

146

Koki AkiyoshiArchitect / Entrepreneur

Creating a Safe Space for Making Mistakes in Roppongi, the Hub of Cutting-Edge Creation

Making with your own hands to connect work and creation

Koki Akiyoshi is the representative of VUILD, an architectural organization that uses digital fabrication and other technology with the goal of democratizing architecture. He advocates the concept of the “meta-architect” and as an entrepreneur, his startup company looks beyond the physical design of buildings to include broader design considerations, such as background material flow. He is currently collaborating with Tokyo Midtown for the MIDTOWN OPEN THE PARK 2023 event with a space entitled Picnic Lab. What is the potential for a future where each individual can be a creator? We interviewed the architect on the relationship between architecture and technology, the scalability of design, and the concept that gave his company its name—a society where living and building are interconnected.

A company established to create a world where anyone can be an architect or a designer

We founded VUILD with the vision to create a world where anybody can be an architect, designer, or creator, by providing the necessary design skills and technology. The company staff is comprised of designers and creators who aspire to make ever better things, as well as those who make their own creations on the side. As a company, the central focus is on incubation. Our business provides support in various forms in order to help ordinary citizens become creators.

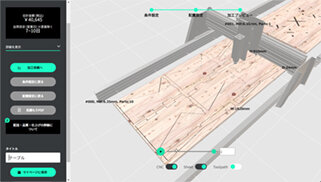

One such service is making the 3D woodworking machine ShopBot available for sale. Two-thirds of Japan's land area is covered in forest, and forestry is deeply rooted in the country's economy. We wanted to provide those who specialize in the lumber trade with a framework that allows them to create and sell furniture and small items even if they aren't designers, and we gradually set up the necessary technological infrastructure. Now, there are 166 ShopBots in use throughout Japan. Another endeavor we started alongside the ShopBot initiative is a service called EMARF. We aimed to create a system that enables people living in the city to casually order furniture and architectural parts to their specifications.

ShopBot

A machine that allows fast and precise woodworking using computer numerical control. Based on design data, a single machine can handle a variety of woodworking tasks such as cutting, fluting, and chamfering. It can also manage complex designs that are difficult to achieve by hand. ShopBot can be used for making small items such as kitchenware to large items such as furniture or parts for a house.

EMARF

A comprehensive cloud service for creating parts based on blueprints that can be done completely online. The obvious use of the service is to make furniture such as desks, chairs, and shelves, but it can also be used to create architectural structures. Factors such as sizing, material, and cost can be simulated pretty much in real time, and the resulting products made in the EMARF workshop are delivered directly to the service user.

Creating a space while the designer offers help and encouragement from the background

At the MIDTOWN OPEN THE PARK 2023 event currently on at Tokyo Midtown, we helped create a space to experience a DIY picnic called Picnic Lab. A key factor in this kind of event is the feeling that all of the participants are actively involved. We avoided giving excessive direction and designed the space in a way that kept the technology in the background.

MIDTOWN OPEN THE PARK 2023

An event held on the Grass Square in Tokyo Midtown between April 21 to May 28, 2023. Picnic Lab is a collaborative effort with VUILD that offers a unique picnic experience in a park filled with creativity. The space provides free use of chairs, stools, picnic trays, and other items created by members of the crafting community EMARF CONNECT. The event also sells picnic meal sets and offers DIY workshops that make use of the EMARF service.

Public spaces generally have finished work created by artists or architects that people are supposed to look at, where there is a clear distinction between the provider and the consumer. Other than coming up with new concepts and businesses that use technology, I think one of our roles is to work with people to create things together in-person. That means the designer takes a back seat, offering help and encouragement to the client as they create a space together. We established VUILD PlaceLab as a team that specializes in that kind of role.

VUILD PlaceLab

A creative team that specializes in the collaborative creation of spaces and venues. It nurtures the client's sense of ownership over the space via process designing through idea and crafting workshops.

Photo:Tatsuya Tabii

We generate some of the designs and data, but intimately incorporating the user in the planning and production process gives them the sense that they are mainly creating the thing themselves, which increases their degree of involvement. With Picnic Lab and other such events, it's important for VUILD PlaceLab to make sure visitors don't become passive consumers.

Design that weaves new relationships between land and materials, as well as between people

More people have been reconsidering their lifestyles since the COVID-19 pandemic in particular, and there seems to be newfound interest in interacting with rural areas and symbiosis with nature. We have gotten more requests of this type where clients want to build their own shop, or employees want to create their own office. The Olive no Mori Gate Lounge, a visitor complex on Shodoshima Island, is a project where we are working with about 100 employees there to construct the shop building. Their employees are directly involved in the process, from stripping the bark from the logs, to drying and processing the lumber, and finally constructing the building.

Olive no Mori Gate Lounge

A visitor complex on Shodoshima Island in Kagawa Prefecture, set to open in July 2023. A local business is working with VUILD to construct new facilities for olive-themed experiences, lodging accommodation, a beauty salon, and a sauna. Under VUILD's direction, the local client has felled roughly 1,000 Shodoshima cypress tree to make logs, actually transporting and stripping the bark themselves. They are also using ShopBot to create the necessary construction parts. About 100 local employees are working to create the complex, specifically sourcing local materials such as by using Shodoshima stone for the foundation.

Our role over there is to organize all aspects of the creative process. We design material flow in addition to the structural design. For example, when we learned that the wood on the island wasn't being used because they didn't have a means of drying it, we suggested devising a way to do so. Since Shodoshima is an island made of rock, we also suggested sourcing local stone material for the foundation. We are providing overall guidance throughout the project, such as by simulating and visualizing wind and energy flow to shape the building, or suggesting procedures for painting the inner walls and assembling the structure in such a way that allows client participation while still ensuring quality.

In collaborating with people to create and develop a project, we believe defining and implementing proper UX (user experience) design is important more than anything else. Designing is not simply structural. It requires a reinterpretation of a location's culture, to be woven afresh with updated social significance. The relationships between people involved in a project also serve as a design consideration. In projects where I'm deeply involved as a designer, such as the Marebito no Ie ("house for the rare visitor") in Toyama Prefecture, I thoroughly explore these factors.

Marebito no Ie ("house for the rare visitor")

A merging of local wood, tradition, and digital technology built this modern gassho-zukuri (a traditional Japanese architectural style where interlocking wooden beams create a steep roof to withstand heavy snowfalls) space for the rare ("mare") visitor. Using ShopBot and local timber, VUILD took charge of its design and construction. The building provides short-term accommodation as a "shared vacation home," proposed as a new accommodation concept that is "more than tourism but not quite settling down." Different visitors to the house come and go as a way of connecting the rural area to cities. It won gold for the 2020 Good Design Award, and was selected as a candidate for the grand award.

Photo:Ota Takumi

Being directly involved in making inspires a perspective that thinks from 100 years into the future

By going through the experience of using island-sourced materials and processing them to build the structure, the Shodoshima employees discovered they were actually capable of doing the project themselves. That tears down the preconceived limitations people impose on themselves, liberating them to be more proactive. That changes the way they think into more big-picture ideas with proper timelines, such as when thinking about what kind of space to make next or how to make use of a forest. I think that change is an especially important thing.

We are collaborating with a local company for the Shodoshima project, so our job is to think of how we can help enhance the abilities of its employees. That inevitably leads to cultural considerations of "What can we pass on to the next era?" and "the need to design for the next 100 years." Businesspeople with long-term perspectives are generally those who are rooted in the local community. That's why it's important to us that we work directly with local people from the area to design experiences for them.

While we think about buildings and other tangible property with a long-term perspective, transforming local wood into products using ShopBot in the short term and thinking about how to grow that as a business is another story altogether. VUILD can function as an immediate business partner, but also provide design with a long-term mindset that can be passed on to the future. I think that dual ability to engage in both business and design is one of VUILD's greatest strengths.

The importance of sharing with children that the world can be even more fun

More and more people are purchasing the 3D woodworking machine, ShopBot that VUILD sells not just for business, but as an investment for future possibilities. In recent years, there have been fewer young people to take over carpentry, and at this rate they say the profession may disappear. Fewer people working with wood means the upstream forestry business is also at risk, and maintaining houses and buildings will become more difficult. Part of what we do and the support we provide stems from wanting to benefit the future of the digital native children of today. We hope to perhaps foster a carpentry equivalent of esports, where digital building becomes prevalent.

Through the company, and also as an individual beforehand, I have conducted numerous workshops for children. I am always fascinated by the unexpected output that comes from these young minds. Children create things that have no existing name. When you remove the limitations of preconceived notions, children start making things that no one has ever seen before, as well as new things that are an extension of their own self-expression.

One time, a child who was about first grade age invented something called the "friendship box." The box had a bunch of holes in it, and the idea was that if people peered through the holes at each other, they would all become friends. Another child made something called a "hello hello bench," a kind of seat for talking to their parents back-to-back, because it can be hard to say how they really feel face-to-face. These are the sort of imaginative inventions you might find in the beloved children's comic series "Doraemon". [laughs]

Friendship box

The work of a child who participated in a VUILD workshop. People can stick their heads into the multiple round holes in the wooden box, making them face each other inside of the box. It creates an exclusive little space for communication that helps them become friends.

Photo: NPO Hama no Todai

I think the reason so many people are into games like Minecraft and Fortnite is because they want to create their own worlds. But constructing actual buildings in the real world is much more daunting. However, if we could frame the creation of physical cities and towns as an extension of building in a game world, I think we could turn that image around.

Minecraft

A video game popular for its flexibility, where players can place blocks to build or try to survive. Often called the digital building block game, it is also used as an educational tool in some contexts.

In ten years, the five- and ten-year-old children of today will be fifteen and twenty years old. What we aim to do with our woodworking machines and workshops is to share with this younger generation that the world can be even more fun. The things they experience in their childhood will become new visions for the future as they grow older. That's why I think it's especially important what the children come in contact now, and how.

Remove the limitation of preconceived notions to provide a safe place for mistakes

Unlike children, grownups unfortunately have an extremely hard time pushing past self-imposed limitations. We actually had a ShopBot available in Roppongi before, and there was a surprising number of people who came to learn how to use the technology but were at a loss as to what to create. This may sound insulting, but I got the sense that a fair share of them were good at making money but not very creatively inclined. Basically, the impression that I get is that Roppongi is a place of business.

In order to remove the creative limitations on people working in Roppongi, I think the important thing is to first figure out how to tie creation into work. In order to do that, developing a creative mindset is the first and foremost priority. I think when you're in a business mindset, you participate in training and talk to consultants and end up knowing a lot, but never actually use your hands to do anything. That's why I think it would help to have a place where you can actually try your hand at making something.

However, I also realize it might be very daunting to create something in Roppongi, where some of the finest works in art and design are on display. There are so many finished works by top artists available for viewing, and Roppongi is a hub for high-level design and creative work. In that sense, you might feel like out of all the places, Roppongi is a place where no mistakes are allowed.

That's particularly why I believe it would be good to have a place where it's okay to make mistakes. A kind of "graveyard for creations," although that might not be the best choice of words. Basically, I want it to be a kind of place that accepts mistakes, where you don't have to succeed, but you do have to use your own hands and have others see your creations for a change. I'm sure that the insight that comes from other people viewing your work will expand your business possibilities as well.

We once had someone who came to see our exhibit leave skeptical feedback. They were concerned that allowing amateurs to become designers would just create a whole lot of trash. While professionals might dwell on imperfections and unrefined aspects of a project, the absence of a safe space, free from such criticism, can stifle creative ideas. Perhaps Roppongi would actually be the perfect place to implement the idea of providing a safe space for mistakes.

The next five years for VUILD will be about building partnerships

I hope our efforts might encourage a change of values. Of course, we are incredibly grateful that people are making use of EMARF at all, but at the moment most users are making what they want for their own use. That's good as an initial phase, but it has been a struggle to get beyond that. I'm finding it very difficult to get people to become what I call "meta-designers" and "meta-architects"-------- those who can take a step back and take an organizing role to draw out someone else's potential. As a potential breakthrough to the next phase, we have started some other initiatives as well.

One such initiative is building collaborative business partnerships. Up until now, there was a clear distinction between the service provider and the user in our relationship with ShopBot customers. We thought eliminating that distinction and working as partners on the same team might expand the possibilities. Just like there are YouTubers who use YouTube as an occupation, we want to make an occupation out of using EMARF and network out to find collaborators who are enthusiastic about committing themselves as "EMARFERS." It has been five years since our establishment, and that's what our goal is for the next five years.

Personally, I'm also interested in generative AI. It's a hot topic at the moment, and we are busy developing so we don't fall behind on this surge of technology. We are currently working on a program where users can output their ideal piece of furniture using EMARF simply by following onscreen instructions and typing in some words. We are currently close to launching an alpha version. Our program's biggest strength that sets it apart from AI image generators and such is that it can output actual physical products.

Generative AI

AI that is capable of learning digital expression based on sample data, automatically generating all kinds of content and things that are novel but still convincing. It has a diverse range of applications, such as creating new images or pictures, drawing blueprints, or writing text. It has the potential of generating completely new output.

Bringing the joy of creating buildings, furniture, and spaces back to the people

The name of our company, VUILD, originally comes from a cross between the root "vi-," which can be found in words like "living" and "vital," and the word "build." It is said that the words for living and building have nearly the same origin. That's exactly the kind of society we aspire to create-------- one where "living" and "making" revolve around each other.

In this day and age, while struggling for basic necessities like food or shelter is less common, maintaining psychological motivation to live can still be challenging. But when you get to do something you want to do, that's fun and brings definite joy. Architects continue to do what they do despite the multitude of struggles they face because it's fun. That enjoyment doesn't just belong to designers and creators and should be more openly available, just like how you feel joy when you make others happy by managing to make a delicious meal.

The world of buildings, furniture, and spaces isn't actually any different. Everyone should be entitled to the joy of creating these things, but that isn't the case in reality. Generally, people passively fit themselves into the townscapes and homes they are provided with and think that things like architecture are too big in scale for them to be involved in. We at VUILD seek to bring that joy back to the hands of the people.

A world where living and building can be discussed within the same scope

I realize that once the ability to create is back in the hands of the people, some professionals might lose their jobs. But ignoring the fear of being misunderstood, I think it's okay if the more superficial designers end up getting eradicated. Even if they are weeded out, they are still left with the role of using their expertise to help the layperson design their projects. Currently, the architect as an occupation evokes the image of someone who comes up with brilliant concepts and iconic designs. In other words, the idea of an architect is limited to someone who simply makes things, and I feel like that trivializes the potential of what an architect can be.

Fundamentally, an architect is "someone who builds." Traditionally in Japan, I think architects had more of a supportive or mentoring connotation, referring to the chief builders and expert carpenters who had to figure out how to supervise and motivate their workers. An architect's role is supposed to include designing how the entire system works in terms of where to source the materials, how to build the project, and how the project will benefit what economic sector. But today, architects don't go that far.

I, too, am a creator, and what I aspire to do is to design with the authorship often associated with the term 'architect,' while also focusing on often overlooked aspects like distribution and economic spheres, as well as helping people develop skills. Society doesn't need that many architects whose egos come out in their work, you know? I believe it would be ideal for only those with unparalleled originality to survive as artists, with everyone else supported by a system that democratizes architecture. The ultimate goal we should seek is to bring living, making, and building back together within the same scope. I think a society where you can talk about design within the same scope as talking about a delicious meal would be much livelier and more wholesome.

Photo location: R-Studio(https://www.miss-ty.com)

Editor's thoughts

In very clear words, Akiyoshi-san responded with big-picture ideas and ways of thinking, something he himself mentioned during the interview. I think the idea that living and building is within the same scope brings a fundamental aspect of human nature back to the people, and is an incredibly large-scale perspective that leads to solving issues in our society. Creating something isn't just about designing its form. This interview reminded me how important it is to actually experience and think about the process, and for creators to expand their values and imaginations to think about what they will generate beyond their current project, and what they should leave behind for future generations.(text_akiko miyaura)

RANKING

ALL

CATEGORY