INTERVIEW

138

Satoru TamuraArtist

Using Ruins to Create Kinetic Artwork on Such a Huge Scale that it Makes the Hands Tremble

The awe of something detached from meaning that simply exists

Satoru Tamura’s style of art is comical and full of humor, yet enigmatically detached from meaning or context, moving people’s souls and posing questions to the viewer. He has a large-scale solo exhibition on at the National Art Center, Tokyo (NACT) featuring the colorful sculptures of his iconic Spin Crocodile series. We interviewed him on the development of his series of spinning crocodiles over time, why he specifically chooses to make things with no meaning, and what “art” is to him.

A spinning crocodile that evokes the sense of the peculiar

Initially, my work with the spinning crocodile just kind of happened. It was something of a coincidence. When I was in my third year of university, we were tasked with a project which I had never come across before, to make "an artistic contraption using electricity." I decided to stick to one rule: I would do whatever popped into my head when I woke up the next morning. Then when I woke up, I came up with "crocodiles spinning" for some reason. I have no way of tracing back to why that happened anymore, so the flyer for the Spinning Crocodiles exhibition on at the NACT says "Don't ask why the crocodiles spin." [laughs]

Spinning Crocodiles, Tamura Satoru

In commemoration of its 15th anniversary, the NACT is holding a solo exhibition that features Satoru Tamura's iconic Spin Crocodile series. The installation includes a large twelve-meter crocodile. The exhibition is on from June 15 (Wed) to July 18 (Mon/Holiday), 2022. Admission is free.

Spin Crocodile

1994

Size: 5,000 x 5,000 x 2,500 mm

Materials: polyurethane, iron, motor, rubber, etc.

Komaba Kunst Raum

Photo: Yozo Takada

The first time I made a crocodile spin left me in quite a shock. I know I'm the one who made it, but it felt like witnessing something very peculiar that had somehow always existed. I couldn't forget that feeling, and I guess I kept making countless pieces to figure out "why making a crocodile spin was so intriguing."

Spin Crocodile VI

1998 (layout revised in 2012)

Size: 5,000 x 600 x 1,200 mm

Materials: polyurethane, iron, motor, rubber, etc.

The Museum of Modern Art, Gunma

Photo: Shinya Kigure

Intriguing before it even moved: the twelve-meter crocodile

My work for the exhibition entitled Spin Crocodile Garden features the series that helped me debut as an artist. I always continued to make crocodiles, and I wanted to try taking my chances featuring just crocodiles. So I'm putting on this solo exhibition at the NACT, but I actually wanted to wait until I was a little older. I imagined it to go down like, "Sir, what do you want to do for your next exhibition?" "I guess I'll spin some crocodiles." "Finally, the culmination of your work as an artist!" But it's happening ten, maybe twenty years earlier than I envisioned. [laughs]

Because the exhibition space in the NACT is so large, I needed something appropriately big and made a twelve-meter crocodile. Once I tried spinning it, it was so huge I just had to laugh. Still, perhaps it looked that big because it was in the yard of my studio. I'm a little worried how it will look in the museum space. On top of that, I made 1,000 small crocodiles as well. I had never made 1,000 pieces at once before, and it really worked my muscles.

I can tell if it works as artwork the moment I power it on

After spending a lot of months and money creating my pieces, whether or not they will work as artwork is determined the moment I power them on. Sometimes I can imagine what the finished product will be like, but I can never tell whether they will be intriguing or not until then. It isn't until the moment they move that I can decide whether they will be one of my pieces. So back in the day, my hands would tremble every time I turned the power on.

There are a number of factors that dictate the line between whether a piece will work as artwork or not. In the case of my crocodiles, one of those factors is speed. Toward the beginning, I made the crocodiles spin once every two seconds in want of the viciousness of speed. Then with every piece, I gradually adjusted the speed faster and experimented to see at what point it worked as artwork.

Then one day, someone advised me that "slow would definitely be better," and I thought, "What? No way." But when I tried slowing down the speed, there came a moment that I honestly thought worked well. In recent years, I find that I'm much happier even if the movement is slow. I used to think speed was so important, but now that I've done a one-eighty and I'm totally fine with slow speed, I have to wonder what happened. Perhaps I rediscovered the appeal within the absurdity of crocodiles spinning, somehow.

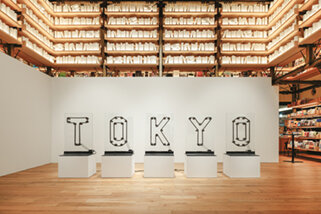

My next project TOKYO machine, which uses power transmission chains to create letters, has a much more complex mechanism. Depending on motor specifications, there was a big possibility that the chains wouldn't move at all. So in the case of this piece, whether it moved properly or not was the first and foremost determining factor, and I felt lucky just as long as it moved.

TOKYO machine

2021

Size: 1,020 x 3,900 x 600 mm

Materials: glass, iron, chains, bearings, motors, etc.

Ginza Tsutaya Books

photo:MAKI Gallery

My motivation is to "reexperience that moment when my hands unexpectedly trembled"

I'm an artist who you might say gets "possessed" by inspiration. The type who already has images of what he should create in his mind and works to bring them to life, one by one. Because I've always worked that way, I feel like I'm gradually running out of things "to do next."

When planning the Spinning Crocodiles exhibition, I had the opportunity to talk to the manga artist Sensha Yoshida and asked him about the time he was drawing Utsurun Desu ("It's Contagious"). He told me that "it felt like some unknown force was making me draw that," and I thought that his experience was similar to mine.

Utsurun Desu

A four-panel manga series by Sensha Yoshida that ran from 1989. Credited for establishing the "non sequitur" comedy manga genre, the series produced video game, anime, and live action adaptations. It has a total of over 3 million copies in print.

It's true that the feeling of being made to createsomething, or the feeling of something "possessing" you from above, isn't something you can experience even if you want to. Even if you think going to a certain place will produce a certain result it doesn't necessary work, and on the other hand sometimes inspiration just pops out of nowhere. I once worked on a piece where the theme was "mountains," and the ideas came rushing forth all at once. I thought about how a mountain would feel most "mountain-like," and in a flash of inspiration decided that I was going to make the most unexpected thing climb a mountain: the mountain itself. If I was going to do that, I'd need a chain here, and a switch here... I could envision the mechanism right away, and from there the whole thing was like working on a plastic model kit. All I had to do was focus on putting the parts together, which was very satisfying.

Wanting to experience the feeling of being driven by something or having my hands tremble in anticipation again is still my motivation for creating things today.

Pushing project rule boundaries

My interest in becoming an artist started in high school. At the time, I liked doing things that were weird or made no sense, and I always pushed the boundaries of what was allowed for my school projects. In middle school, my teacher would always react in a way that said, "Why the heck would you do such a weird thing?" But once I was in high school I started receiving some more positive reactions, which was big for me.

Until I was in high school, I had no interest in drawing, either. I thought of contemporary art as "that genre where they do weird stuff," and when I flipped through books on it I was shocked every time, thinking, "I didn't know you could do that." For example, "What is this? Video sculpture? That's allowed?" Perhaps seeing that kind of thing gave me a strange sense of confidence, such as "I can see myself succeeding in something like this. I would totally hold my own."

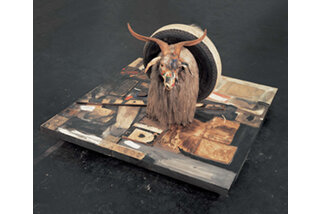

The first most striking artist I remember is Robert Rauschenberg. The particular work was a combine painting that had a stuffed goat on top of a painting, which I remember because it was featured on the cover of my fine art textbook or something at the time. I remember thinking, "Isn't this stunning?" and also, "I am great at this kind of stuff."

Robert Rauschenberg

An American artist representing the Neo-Dada movement. He mixed two-dimensional and three-dimensional materials to create "Combines," which transcended genres such as painting and sculpture.

photo:Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Detaching motifs from meaning and purpose brings them closer to truth

My work detaches motifs from meaning and purpose and simply shows them moving. I realize this sounds juvenile, but think that brings them closer to truth. Things that simply exist seem awe-inspiring, somehow.

Maybe it's like Genpei Akasegawa's concept of Thomasson. For example, when I see a utility pole stripped of all its wires, disconnected from everything and standing in the middle of a wasteland, I find that awe-inspiring. Something that was probably used for something in the past, but now simply exists. Something that looks like it's on the path to decay. That's the kind of thing I hope to make. The spinning crocodiles are kind of comical in a way, but all I want is for viewers to think, "What the heck?"

Thomasson

A type of conceptual art proposed by Genpei Akasegawa and others. It refers to a part of a building that no longer has any use, such as stairs that end abruptly and serve no function. The practice of observing urban environments in the manner of fieldwork eventually led to the concept of "Street Observation."

Around 2014, I had the opportunity to show my Spin Crocodile again for the first time in a while, and one of my friends from university told me that it hadn't gotten old at all after all these years. Together, we thought about why that might be. We eventually concluded that this might be because it was detached from meaning or context, making it difficult to talk about and therefore difficult to evaluate.

For my exhibition at the site of the old Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries shipbuilding factory in Toyosu, I took an anchor that is usually supposed to function as a weight and perforated it to create a lightweight anchor. The work is aptly called Light Anchor. It's a public art monument where I thought something just "clicked" by turning the object's meaning on its head. When I'm given a specific theme as in this case, I enjoy taking the context apart.

Recreating "crazy artwork" seen in Liverpool for Roppongi

Before COVID, I traveled about twice around the entire globe for art fairs and exhibitions. I visited many cities such as Miami, Basel, and Hong Kong, but it was in Liverpool that I accidentally came across an amazing piece of artwork. It was a crazy piece where a circle cut out of an abandoned building in the city would rotate. I was so thunderstruck it made me dizzy. It was done by an artist named Richard Wilson, and a part of the actual building really moves.

Turning the Place Over (場の回転)

Work by British artist Richard Wilson. A piece of an abandoned building spanning two floors is cut out and rotated 360 degrees. It was part of the 5th Liverpool Biennial in 2008 and was shown until 2011.

©Richard Wilson

The piece made use of a building that was scheduled for demolition, and there were normal pedestrians below and everything. The technology required to cut the circle out of the building, the technology required to rotate the wall... I couldn't believe such a thing was permissible, and I was perplexed and stunned by everything.

If I were to do something in Roppongi, I would want to do something this outrageous. When making kinetic artwork in Japan, it has to be done indoors for the sake of safety measures. But outside of Japan, artists do crazy stuff like this once they get to some level of prominence, and I always think I need to follow their example of pushing boundaries. If I ever make something at that kind of scale, my hands won't just tremble when I power it on. I think I might faint. I might even go home without ever pressing the switch. [laughs] Just imagining it makes my heart pound.

Photo location: Spinning Crocodiles, Tamura Satoru (Venue: National Art Center, Tokyo / Special Exhibition Gallery 1E, Dates: June 15 - July 18, 2022)

Editor's thoughts

Giant, colorful crocodiles spin, the machines moving with grinding creaks... Looking at Tamura-san's work puts me into kind of a pleasant, mindless trance that reminds me of when I used to play by pouring water on my head as a child or when I see the vast ocean stretching out in front of me. I used to question whether it was okay for me to feel that way as someone viewing art, but with this interview it seems to finally make sense. Perhaps that's how one feels when looking at something detached from meaning or context and simply exists before you.(text_koh degawa)

RANKING

ALL

CATEGORY