INTERVIEW

136

Ryoko AokiNoh Singer

A Contemporary Music Concert in the City Where the "Everyday Becomes a Journey"

A new way to present Japan's cultural inheritance of noh theater

Captivated by the depth of utai, the vocal singing part of traditional Japanese noh performance, Ryoko Aoki has dedicated herself to pursuing it. However, her work does not simply pass on the traditions of the performing art. With great respect for the traditions of noh, which is a cultural inheritance unique to Japan, she also uses utai as a medium to create a new artistic form. From 2010, she has collaborated with leading global composers of contemporary music to host "Contemporary Music × Noh," a commission series designed to draw out the appeal of utai from different angles. Beginning with a stunning debut in 2013 at the Teatro Real opera house in Madrid, Aoki has performed with multiple prominent European orchestras and ensembles such as the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and the Ensemble intercontemporain, constantly presenting new forms of utai. We interviewed her on the path she has pursued, the art she encounters overseas, her thoughts on art, and the future of Japanese traditional art.

Suntory Hall is a place of promise and excitement, my "special place"

I'm originally from Oita Prefecture. When I came to visit Tokyo for the first time with my family, we stayed at the (former) Tokyo ANA Hotel in Tameike-sanno. We visited the adjacent Karajan Plaza, which is where Suntory Hall, the hall where we just did a photo shooting, is located. Back then, they where shooting a live TV show, and it felt so urban. I remember being very excited to be there. Later on, I returned to Tokyo to enter university, and I spent my days going to concerts at Suntory Hall. Even now in the summer, I go there almost every day. Suntory Hall has always been a place of promise and excitement for me, and my "special place" that still gets my spirits up every time I visit.

Suntory Hall

A world-class concert hall built in 1986 with the concept of pursuing "the world's most beautiful sound." It was also the first hall of its type in Japan designed in the vineyard style, with cascading seats surrounding the stage like terraced slopes. The style is known for providing musical experiences where performers become one with the audience both acoustically and visually for a shared feeling of immediacy. The hall also includes charmingly playful references to the Suntory Group, such as the use of white oak typically used in whiskey barrels for the interior walls and a chandelier above the stage inspired by champagne bubbles.

PHOTO:©SUNTORY HALL

As such, it was so moving when I first got to stand on that stage in Suntory Hall. It was for the Suntory Hall Summer Festival 2021, where we put on the opera Futari Shizuka―The Maiden from the Sea composed by Toshio Hosokawa. I had performed in the opera's world premiere in 2017 with the Ensemble intercontemporain in Paris, where the ensemble is based. We did subsequent performances in Cologne in Germany, Toronto in Canada, Tongyeong in South Korea, and New York in the USA before finally holding the Japan premiere at Suntory Hall.

Suntory Hall Summer Festival

Suntory Hall's annual summer music festival that attracts large audiences every year. The festival concentrates on contemporary music and offers rare opportunities to hear performances by some of the most renowned musicians in the world at the forefront of innovation. While people often assume contemporary music to be difficult to understand, the festival is a chance to experience it in a fun, casual way at reasonable prices. A theme composer is chosen every year, and will be Isabel Mundry for summer 2022. The festival is planned for the week leading up to Sunday, August 28, 2022.

PHOTO:©SUNTORY HALL

Futari Shizuka―The Maiden from the Sea, an opera composed by Toshio Hosokawa

Helen, a refugee girl who is washed up on the shores of the Mediterranean after losing her young brother, is possessed by the spirit of a 12th century Japanese dancer named Lady Shizuka. Once the mistress of a samurai commander, Shizuka had been pregnant with his son when the commander was subjugated by the ruler of the era. Their son was killed and buried in the sands of a beach. Transcending space and time, the tragedies of the two women at the mercy of inescapable violence overlap and their voices gradually unite as one. This opera has received high praise all over the world with its outstanding union of a soprano singer and Ryoko Aoki's utai. The photo is from its Japan premiere held at Suntory Hall.

PHOTO:©SUNTORY HALL

I had actually always used a PA system to amplify my voice for Futari Shizuka―The Maiden from the Sea, but I sang for the first time without one for the Suntory Hall performance. Mr. Hosokawa had initially been worried that my voice may be hard to hear over the orchestra, since the orchestral register just happened to overlap with mine. But the hall's acoustics were just amazing. Yasuhisa Toyota, the acoustician for Suntory Hall, has designed the acoustics for numerous concert halls all over the world. He creates excellent acoustic environments with respect for the architect's vision. He actually came to our performance, and was very happy to report that he could hear me very well even without a PA system.

Captivated by the profound and fascinating nature of utai, considered the most important part of noh

Futari Shizuka―The Maiden from the Sea is based off of playwright Oriza Hirata's contemporary adaptation of the noh play Futari Shizuka. The script inspired Mr. Hosokawa's composition that combines noh utai, soprano, and orchestra. When I mention "noh," I imagine most people think of actors dancing with noh masks. That was my impression at first as well, and because I have danced ballet from a young age I went to my first noh lesson fully intending to dance. But I was taught there that I should sit down and learn utai first, because that is the most important element in noh.

Utai

Noh acting is made up of utai (vocals) and shosa (movement). Utai is the vocal element of noh, which includes those sung by characters such as shite (lead role) or waki (supporting role), as well as those sung by jiutai (chorus). All vocal sections including dialogue are all called utai. With its writing, vocalization, and intonation, utai is also distinctive for not only telling the story but also evoking a poetic feel (reference: Culture Digital Library).

PHOTO:©427FOTO

I always liked using my voice, but even as a child I hated that my voice was low and incapable of producing girl-like high tones, as well as how I had trouble singing in key with others in a chorus. But in utai, it's better to have a lower voice. The voice I had been so self-conscious about was actually a great match. As I went through more lessons I saw how fascinating the unique singing technique was, and eventually came to find utai to be very profound and compelling.

Becoming a "noh singer" with faith in utai's potential and versatility

Afterwards, I was learning noh at Tokyo University of the Arts but I wanted to learn about it academically in addition to practicing it, and went on to study abroad at the University of London. At the time, the thing I most struggled with was examining noh objectively. Because I was in the world of noh for a long time, there were aspects to which I was too close to see properly. When I was writing my PhD thesis in English, my teacher asked me repeatedly why I couldn't write objectively. But over the course of writing my 600-page thesis, I started being able to look at things more objectively. When I had been learning noh, everyone around me was very knowledgeable and quick to understand anything I would be talking about, so I never had the opportunity to explain things to people who were unfamiliar with noh. But most people overseas don't know about noh, so I had to start by explaining the basics. Thinking through how to explain each aspect to someone with close to no knowledge on the subject helped me to develop the objective perspective I needed.

From my student days, I performed in crossover collaborations of noh with other fields, but my encounter with Joji Yuasa was a particularly significant event. A composition he wrote a very long time ago is an ensemble of utai and western instruments entitled "Snow Falling Down," which had been performed once in the past. One day he was looking through some things at home when he came across the sheet music. He wanted to revive it for the first time in decades and asked me when he was looking for someone to sing it. In singing "Snow Falling Down," my excitement of realizing that western instruments can complement utai, and that utai might actually be quite versatile led me to look beyond the obvious choices of becoming a noh performer or a researcher and pursue an alternate path as a noh singer.

What sets utai apart is the very unique and distinctive vocalization it requires that cannot be produced by a vocal performer in Western music. Although it is usually accompanied by ohayashi (accompaniment using traditional Japanese instruments), I was very interested to think about the possibilities if utai was to be performed with an orchestra or an ensemble. Most importantly, I wanted more people all over the world to discover the appeal of utai. That's what led to my current performance style, where I work with contemporary musicians and composers to create pieces that use utai that I perform internationally as a noh singer.

New music that results from unexpected interpretations and misunderstandings is what makes the current endeavor truly interesting

When thinking of fusing utai with contemporary music, the first obstacle I came up against was how the musical notation and structure were fundamentally different. Noh music does not specify pitch or rhythm. While there are utaibon (utai books) that include both the musical notation and the script, noh performers generally learn how to sing a piece directly from their masters, which is different from how Western music is an art form that primarily relies on musical notation to pass on its pieces. In addition, utaibon are obviously written in Japanese, which makes it challenging for overseas composers to take on. That's why I transcribed utai to Western musical notation, created digital sound files, and created a website in both Japanese and English entitled "Study of Noh Chanting for Composers" that explains what utai is and how to compose music using utai.

This website helped composers understand utai much better. However, a composer discovering utai for the first time obviously cannot have the same understanding as a Japanese person who has studied noh for many years. This sometimes results in unexpected interpretations or misunderstandings. But I think that's what makes this endeavor so interesting. Composers treat utai purely as musical material, so they tend to compose music with attention to the aspects of utai that they find interesting.

For example, this past February in Madrid I performed with the Spanish National Orchestra in the world premiere of "Hacia La Luz" by José María Sánchez-Verdú, one of the most prominent composers in Spain. He told me to sing with emphasis on the kind of timbres that Western music singers would never produce, by which he meant utai's distinctive vocalization that sounds like it has a constant vibrato. Utai also often has the sound "no~" rising from a low pitch to a high one, but to a noh performer, the high pitch is the target and the lower pitches beforehand are kind of a preparatory phase. However, there was a composer who really loved the preparatory part and create a piece with emphasis on that.

To begin with, I had no interest in trying to superficially match the ancient art of utai with conventional Western music. What I wanted wasn't to emulate noh or reproduce it, but to use utai to create an entirely new form of art. That's why I want my voice to be treated as a musical ingredient. What I want is for composers to use the ingredients to create their own original piece. When I listen to the finished piece, I can tell where the composer's interest lies in and how they interpreted utai. Those perspectives lead me to rediscover things about utai that I never noticed before. Unexpected misunderstandings by composers are definitely not a minus, and the new creations that result are what make things truly interesting.

What I find overseas is an abundance of "hooks" for encountering new things

Mainly through my "Contemporary Music × Noh" project, I collaborate with contemporary composers to create new pieces that use noh utai and perform them as a noh singer. However, I imagine both utai and contemporary music can seem intimidating and complex. I for one knew nothing about noh when I first started, nor did I know much about contemporary music. But my personality is such that I would rather dive into something and try it first rather than study it (laughs).

Contemporary Music × Noh

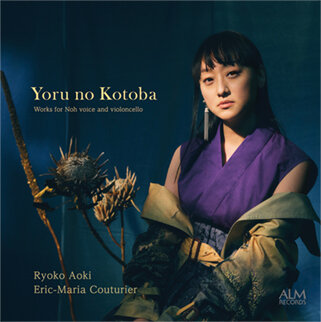

A series that commissions internationally active composers from various countries to compose a piece using noh utai. 42 composers from 19 countries have produced music for the project so far, creating an innovative fusion between contemporary music and utai. The resulting creations have received widespread attention, with invitations from distinguished orchestras around the world to put on performances. During the pandemic, Aoki organized remote real-time performances on YouTube Live with European musicians, entitled "HO NOH-Pray for an end to the COVID-19." Using the same method, Aoki in Tokyo and Éric-Maria Couturier in Paris performed a remote session in real time, which was recorded simultaneously in both places to produce the album Yoru no Kotoba.

PHOTO:©RYO HANABUSA

The same goes for when I first started on this project. It was very difficult to find a shared language with composers versed in Western music, and there were times we did not fully understand each other. But as I proceeded with an attitude of just giving things a try and figuring that even if we could not understand each other through words, singing the composer's music would help me understand them, I feel like we gradually developed a shared language for communication. There are definitely many breakthroughs that can happen and things you can learn by actually giving things a try. So I hope people will not worry too much that utai and contemporary music are too hard and just try listening to them.

Unfortunately though, I think that perhaps there are not many opportunities to encounter unfamiliar things in Japan. When I perform overseas, I feel that there is an abundance of "hooks" that get people to encounter new things. I traveled to Spain this past February to perform the world premiere of eminent Spanish composer José María Sánchez-Verdú's "Hacia La Luz" with the Orquesta y Coro Nacionales de España (Spanish National Orchestra) at the Auditorio Nacional de Música (National Music Auditorium) in Madrid. There, I saw that there were many opportunities around the city to just casually come in contact with contemporary music.

José María Sánchez-Verdú「Hacia La Luz」

Aoki performed this piece with the Spanish National Orchestra at the National Music Auditorium in Madrid from February 11th to 13th, 2022. Spanish composer José María Sánchez-Verdú composed this large-scale orchestral work to be performed by a female soloist (performed by Aoki), female chorus, male chorus, organ, and orchestra. The piece is based off of a poem by the ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides and uses music to tell an epic tale of shamanism.

PHOTO:©José Luis Pindado

For example, a major Spanish bank that owns a private music hall puts on a free contemporary music concert once every month. I had the opportunity to perform there once myself. They have a precious Francisco de Goya painting there that they only bring out on concert days to hang up behind the performers. Of course there are many people who come because they love music, but I'm sure there are some who come because they want to see the work by Goya. That may be what leads someone into a newfound interest in contemporary music, or makes someone want to go to more concerts. Those kinds of hooks are very prevalent overseas.

It stems from being conscious about constantly evolving one's culture

Madrid is one of my favorite cities. The biggest reason is that the food there is delicious, but it's also appealing as a city that offers a lot of encounters with art. There are numerous museums that have works by famous painters such as Goya, Diego Velázquez, and Pablo Picasso. Some of them, such as the Museo del Prado (Prado Museum) and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Queen Sofía National Museum Art Centre), provide free admittance in the evenings, making them incredibly accessible. In addition to the usual concert halls and opera houses, concerts are sometimes held at museums as well, where many people attend on an everyday basis. People are very warm and friendly there, and sometimes when I was walking on the street after a show people would call out to me to tell me they enjoyed my performance. That made me very happy.

There are many inspiring cities other than Madrid, and I think Paris is another city with a wonderful environment. The famous Palais Garnier opera house sits in the center of Paris. The fact that it is such a historic location but stages very innovative work seems incredible to me. One time, it staged an opera by an Italian composer of contemporary music named Salvatore Sciarrino. It involved novel choreography by American choreographer Trisha Brown set to noise-like sound from wind instruments that went on and on. It's a wonderful experience to come across work that makes you go, "Wait, what is this?!" It's also very lucky to be able to encounter the forefront in music. When I'm overseas, a casual encounter like that is possible without even trying.

In addition to producing new operas by current composers, they also update old pieces in new ways. In Europe, people are inherently conscious about constantly evolving their culture. Toshio Hosokawa's opera Futari Shizuka―The Maiden from the Sea, which I have been performing worldwide, was also created with that motive in mind. Based on the noh play Futari Shizuka, Oriza Hirata wrote the script with reference to hostilities and acts of terror happening at the time, and the opera was originally created with the assumption that it would be performed in France. Now with the many refugees once again due to the conflict in the Ukraine, the story has renewed relevance. In other words, arts and culture serve as media that present ever-relevant cautionary tales to contemporary audiences.

I feel like the concept that tradition should be preserved exactly the way it was in olden times is unique to Japan. For example in Europe, people do not think of music by Bach and the new music of today as completely separate things. They think of the music by Bach as the foundation that led to the new music that is made today, and that they are connected. And at the end of the day, when people encounter art in town they enjoy it as a present-day experience. I am very attracted to that way of thinking in that kind of environment, and I think that's why I seek to create work with composers of Western music.

Spending each day as if on a journey will change your perspective

I mentioned that perhaps there are fewer opportunities in Japan to hook people into unfamiliar things, but I believe that if you spend each day as if you're on a journey, it's bound to change your perspective on things. Just the way you are constantly on the lookout for things to see and places to go when you're on a trip overseas, I think it would be nice to think of daily life as if you're on a journey. We don't live in an empty city. We live in one that offers constant opportunities for sightseeing and first-rate cultural experiences. If we spent our days with that in mind, I think we would notice that there are more hooks around than we think. Specifically, there are concerts like the Suntory Hall Summer Festival where you can discover music by some of the world's best musicians and ensembles with more reasonably priced tickets than usual. After all, hearing great music in person is an incredible thing.

I think it would be interesting if the hooks would increase in scale. For example, say musicians from the Summer Festival would do small performances at Roppongi Hills or Tokyo Midtown, and if passersby thought they wanted to hear more, they could go straight to Suntory Hall by shuttlebus or something. I also think a mobile concert would be really neat. It would be fun if musicians took over the Ando architectural design of 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT for a day and visitors could hear them playing in various places throughout the venue. There was also the portable concert hall Lucerne Festival ARK NOVA designed by Arata Isozaki and Anish Kapoor, which was also very appealing. The project started in the Tohoku region, but it was also set up on the Tokyo Midtown Grass Square at one point. I think it would be interesting for another concert hall like that to be set up in the center of Roppongi by some international architects.

Lucerne Festival ARK NOVA

A huge portable concert hall that was created to support the recovery in the aftermath of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. The collaborative design between Arata Isozaki and Anish Kapoor results in a hall by blowing it up like a balloon. At the Lucerne Festival ARK NOVA 2017 in Tokyo Midtown, concerts, film screenings, and talk events were held in the venue.

I have the impression that Roppongi is a place where art-loving people gather, so a collaboration between art and contemporary music might be fun. In Paris, they hold contemporary music concerts in places such as the Musée du Louvre, Musée d'Orsay, and the Fondation Louis Vuitton (Louis Vuitton Foundation). In Roppongi I think it would be interesting if contemporary music concerts could be held in places like the 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT designed by Tadao Ando, the Suntory Museum of Art designed by Kengo Kuma, The National Art Center, Tokyo designed by Kisho Kurokawa, and the Mori Art Museum.

In hopes that Japan's traditional cultural inheritance will change form to live on somewhere in the world

Personally, I am very interested in the concept of JAPAN VALUE. So far in Japan, designers and creators have expressed distinctively Japanese products and aesthetic concepts with contemporary sensibilities. I think what I am doing is similar to that. It goes without saying that protecting tradition is important and worthwhile, but personally, I think there is something very romantic about Japan's cultural inheritance changing form to persevere on a global scale. For example, Japan's traditional sushi cuisine changed form to become the California roll, and Italian pasta gave birth to the Japanese "spaghetti napolitan."

For example, if I were to visit Europe and happen to see an orchestral concert where a non-Japanese person was singing utai, I think that would be very moving for me. That's the kind of future I dream of, as I transform Japan's cultural inheritance through utai in hopes of providing opportunities for producing amazing works of art.

Photo locations: Suntory Hall Main Hall (photo 1), Foyer (photos 2 to 4)

Editor's Thoughts

In a sense, Aoki-san's endeavors are extremely innovative in a way that completely breaks through the Japanese idea of tradition. But not in a destructive way. From her tone and what she talked about in the interview, I got the very strong impression that she is motivated by a desire to present utai to the world that stems from a deep love and respect for noh and utai. Her work also offers new insight into the Japanese tendency of dividing the old from the new. She is a strong, elegantly poised woman, but it was also charming to see how her eyes sparkled when she talked about food and sweets. There was also appeal in how she was so natural and friendly that you might almost forget she is an eminent professional who is active on the global stage.(text_akiko miyaura)

RANKING

ALL

CATEGORY