INTERVIEW

131

Satoshi YoshiizumiDesigner

Rediscovering the Relationship Between Humans and Nature that Exist in Human-Centric Cities

Building relationships with the region to cultivate distinctive culture

After studying engineering at the School of Engineering at Tohoku University, Satoshi Yoshiizumi gained experience at the design office nendo before establishing TAKT PROJECT. Constantly establishing new questions for “self-driven research,” he has always proposed new values for design with a broad vision and an unbiased perspective. In November, he put on an exhibition in Roppongi’s new office/gallery/shop complex THE MODULE roppongi, entitled ALLIED FEATHER&DOWN × TAKT PROJECT “route to root —retracing the story of down.—” Starting with the topic of that exhibition, the interview with Yoshiizumi turned to the subject of “intellect” in design, the value of cities in the COVID-19 pandemic, and his current project in the Tohoku region.

Digging into the materials allows a look at the bigger picture

Personally, I've always had an interest in materials, and I often take a deeper look at them when I conduct research during my design process. The ALLIED FEATHER&DOWN × TAKT PROJECT "route to root —retracing the story of down.—" exhibition at THE MODULE roppongi was in collaboration with the feather down supplier Allied Feather + Down. I thought it was interesting that it showcased a material supplier instead of a fashion brand. When we first started talking about the project, I was just genuinely intrigued by the idea of using down jacket material.

Cultural Synthesis in "THE MODULE roppongi"

Cultural Synthesis in "THE MODULE roppongi" is currently underway as a special project for THE MODULE roppongi, a new complex in Roppongi with shop, showroom/gallery, office, and SOHO floors. The project brings together diverse people, concepts, and things in exhibitions by five groups of creators to showcase the complex as a creative place that stimulates inspiration. Satoshi Yoshiizumi was involved in the second exhibition group.

Venue: THE MODULE roppongi (#205 2F, 7-21-24 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo)

Dates: Friday, October 8 to Sunday, December 26, 2021

https://6mirai.tokyo-midtown.com/event/cultural_synthesis_in_the_module_roppongi/

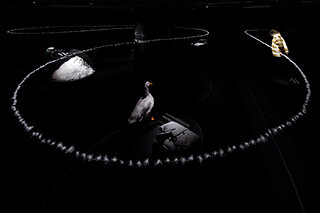

ALLIED FEATHER&DOWN × TAKT PROJECT "route to root —retracing the story of down.—"

An installation that retraces the business journey of Allied Feather + Down as they manufacture feather and down material. The exhibition starts with the physical design of the down jacket and backtracks all the way to gooses and ducks, scattering the "route" with associated stories along the way. According to Yoshiizumi, "I hoped to capture the route as a single landscape when designing the space for the exhibition. Down is so delicate that they sway with the slightest movement of air from people walking by. I thought it would be an interesting experience for visitors to see a physical element that can't be controlled, much like nature itself, appearing for a limited duration in metropolitan Roppongi."

Photo: Daisuke Ohki

Theoretically, the journey of manufacturing a product should be connected along an overall route, from what the materials are, how the product is formed, where it is sold, how it is bought, to where it ends up. But in actuality, we only highlight certain sections of that journey, and I think society had long been focused on selling the superficial aspect of "what a product is like." But now that trend is shifting, and we need to expand our perspectives a bit. In that sense, I believe it's very meaningful to have a project that focuses on the materials as a theme and to have a supplier be involved in an exhibition.

I think current issues such as sustainability and animal free (no animal-based materials) practices tend to be taken out of context and proliferate as biased content or empty catchwords. Sometimes, you need to look at the big picture to truly understand or evaluate a practice. By visualizing where the materials come from and where they go, I hope that this exhibition to some extent served to highlight the importance of expanding one's perspective to gain proper insight.

The importance of "self-driven research" that isn't about short-term business

Whenever we want to create some new thing of value, I think more often than not we need to trace the manufacturing process back to the beginning. When a large manufacturer makes a product, decisions about production volume, price, and what factory will be used for production are usually all predetermined. Simply providing a design at the very end within that system doesn't fundamentally change anything. This is probably true in any other industry, so it's important to dig deeper into what aspect to change in what seems to have become an unspoken rule in society. How far back do we need to retrace to make a change that affects the end result? That concern leads into the significance of our Self-Driven Research projects.

As a design studio, TAKT PROJECT operates by taking on work from clients. But in terms of business, most of these projects are short-term or at the very most medium-term. Always creating within that kind of timeframe raises the concern that perhaps we are not really approaching the central issues that the designs are supposed to address. That's why we always want to be in the mindset of considering what the potential results are in the long-term. It's too late to start the thinking process after taking on a job, so constantly conducting research on the everyday things we notice is at the root of the Self-Driven Research concept.

In my mind, each project for a client is a living creature— a raw manifestation of reality. It's where I gain the insight that I dig into for my research, and I believe pursuing client work alongside my Self-Driven Research projects is vital for creating value as well as for my mental wellbeing as a creator.

Potential for design that incorporates the uncontrollability of nature

Some of my recent self-driven research materialized as a solo exhibition in Milan, Italy entitled glow⇄grow. It had an installation hung upon entering the venue that looked like icicles, actually made of resin. It used a type of liquid resin that cures with UV or visible light, and dripping it onto an LED light hung from the ceiling made the resin solidify into icicle-like formations.

glow⇄grow

An installation presented during Milan Design Week 2019 as Yoshiizumi's first major overseas solo exhibition. It displayed the process of solidifying light-curing resin into growing icicle-like formations using programmable LED light. According to Yoshiizumi, "More people tend to show interest in this kind of work overseas but as Europe is very environmentally conscious, it's true there are people who criticize the use of plastic and resin materials. Of course it makes me happy when I get positive feedback, but I'm also interested in negative comments because I can see the differences in how people perceive things. Presenting work is part of my research, so the important thing is for my work to get some kind of reaction out of people."

Photo: Takumi Ota

From a design perspective, industrial products made from plastic are representative of manmade objects that need to be formed with precision control. However, I feel like the very idea that humans can manufacture anything with perfect control goes against humanity's relationship with nature. For glow⇄grow, I realize that using manmade resin and controlling manmade lights results in artificial icicles made from resin. However, nobody can decide what kind of icicle formations will result. Their growth varies based on gravity, wind, and light in the environment, making it impossible to control how the icicle form.

I personally believe that the important thing is to create with that kind of influence from nature. Instead of using technology to eradicate nature, I want to explore how to connect with nature in creating appealing work and situations, and investigate the potential for design outside of the context of humans creating things. This glow⇄grow installation was a sort of study into that concept.

In terms of sustainability, plastic is generally presented as evil. It's true that plastic has the problem of not being biodegradable, but I think that the real issue stems from humans establishing the notion that plastic is inherently a disposable material. In other words, the problem lies in the fundamental way humans think about the material. That's why I think when designing anything, it's just as important to understand how systems, definitions, and human thought is established as it is to actually create.

Ambiguous impressions presented as intellect

I have an engineering background, so my education mostly dealt with logical ways of thinking. Modern science is built on the logical analysis of each element of the world in a systematic manner and the accumulation of what humans come to understand through that process. However, each understanding is essentially a definition that humans establish in retrospect, and there are many things that we have yet to fully understand. We don't have a grasp on all phenomena.

During my student days, I developed a keen interest in those evasive things that are beyond the world of logic. That interest has led to my self-driven research and TAKT PROJECT's concept of design as a "new intellect." Fundamentally speaking, I think society tends to associate logical thought with the word "intellect." When a person talks about their work in a logical manner, people describe that person as "intelligent" or "smart." In contrast, I think a person who explains things intuitively, such as "that feels really nice," or "I just feel like this part isn't working," wouldn't be described in those same words. But I personally think that the ability to have those kinds of ambiguous impressions are an important part of human intellect.

Particularly in urban areas where diverse people tend to interact, communication must be built on common rules to function, so I think ambiguous things that have no correct answer tend to get eliminated in that context. Our hope is that someday, the world will be a place where people see value in both the logically-minded people and the people who believe that some things go beyond logic, allowing both groups to discuss issues together. To attain that goal, it's important for us to communicate new ideas in the form of physical creations or experiences. I think having that potential is one of the great things about design.

The potential for breathing space due to not meeting people

TAKT PROJECT is currently conducting a new research project based in the Tohoku region. I believe culture in Tohoku is originally built on its relationship with nature. Or rather, it may be more appropriate to say "the Tohoku of the past," since Tohoku today has a lot of urban areas. For example, traditional Tohoku hunters called matagi and the Ainu people who come from Hokkaido have their lives deeply connected to bears. It's not a matter of comparing city life to their way of life. I just think that the very way they perceive nature is fundamentally different.

Tohoku Research

A research project based out of the Tohoku Lab in Sendai that involves TAKT PROJECT spending about three days once a month visiting various places in Tohoku, with a different objective each time. They conduct field research as part of this Self-Driven Research project. Through investigating the philosophies and lifestyles in the somewhat secluded region of Tohoku, they also contemplate how they might make use of local materials to create.

Photo: Shintaro Kurihara

In contrast, culture cannot exist in the city without the people. Given this, perhaps the city loses its significance more than anywhere else in the pandemic. Because its culture is built on relationships between people, it takes a fundamental blow when those people cannot meet in person. But personally, I think there were some upsides to the situation. Looking back, I think there were plenty of times when people probably didn't need to meet up, or it wasn't necessary to gather. But because of the pandemic, being forced to avoid physical interactions has provided a new kind of breathing space for the people who tend to gather and socialize to an excess.

In other words, everyone has been given the opportunity to reduce their interpersonal connections and connect with something else entirely. In the context of technology or design, communication described in a positive light is almost always about connecting with other people. But that connection doesn't necessarily have to be with other people. A little girl interacting with the grass and the trees is very sweet, and I think a connection with nature in the home, such as with a pet, is a wonderful thing as well. Now that everybody is separated from each other, they now have the option of spending time in relation to nature rather than connecting with other people. At the same time, we should be thinking about how to enrich the time we do spend connecting with others, and what it means to do so.

The appeal of the Tohoku region that doesn't exist in central urban areas

I optimistically hope that coming from Yamagata Prefecture, which is part of Tohoku, people might forgive me for saying that Tohoku is a remote region on the outskirts. Historically, no capital has ever been set up there that has survived to the present day, making the Tohoku region a constant outlier. In contrast, Kyushu is close to mainland Asia and was historically home to many powerful families, and as we all know the capital relocated from Nara to Kyoto and eventually settled in Tokyo. But there are many current problems, environmental issues being one of them, that I feel cannot be addressed when limited to the urban or "inner" mindset of those central cities, so I think we might be able to get some different perspectives from the "outside." In that sense, the Tohoku region has great appeal and is very intriguing to me.

Asides from being "on the outside," I also think the Tohoku region is isolated, in a way. The simple fact that it has a snowy climate is a major factor. The snow cover forcibly closing off the region for a good portion of the year may have given rise to a unique culture with different ways of thinking and interacting. In modern times, people place value on everything being open and connected, so I think it's very unusual to have a region where people can physically experience a relationship with nature governed by a cycle that repeatedly opens and closes. I don't mean to dismiss Tokyo or the "inner" regions when I say this. I make my visits to Tohoku because I want to understand more about both ends of the spectrum.

Distinctive culture derives from connecting with the region

I have set up a base in Sendai as the project's hub to travel all around Tohoku. Although the other studio members think I must be just going on trips for pleasure (laughs), I actually go to conduct research with a different objective each time.

Actually, I was in Akita Prefecture until just yesterday. I had two objectives this time, and one of them was "to meet a matagi." The idea behind this was very straightforward, to go and find out about life in the mountains. The other objective was "to do research on crude oil sourced in Akita." I had only ever thought of the Middle East when it came to sources of oil, so the fact that there are oil fields in Akita is interesting in and of itself. Crude oil as a material is symbolic of the current age of globalism, but if I were to create something using oil from local sources, it would represent a connection with the region even if the result wasn't immediately identifiable as a local material, like plastic, and I think it would offer some insight from a different perspective.

Akita's crude oil

An oil field in Akita Prefecture that Yoshiizumi visited on a Self-Driven Research project based in Tohoku. The Toyokawa oil field that supplies 4% of Akita's natural gas produces crude oil along with the gas. According to Yoshiizumi, "The oil source is in the mountains. This may be obvious, but crude oil comes from nature, and hearing about the process makes it sound similar to agriculture. It started to feel more like an act of harvesting rather than that of drilling and extracting. That was kind of intriguing."

Fundamentally speaking, I think we are in an age where people's connections to the natural region they live in has gotten sparse. I'm personally fond of the word "culture," but in relation to art and design people always say that "Tokyo is where you find culture." They're not wrong, of course, but I think rural areas are actually where culture is richer and more distinctive than in cities. I hear the phrase "culture is to cultivate" a lot, and if you take that to mean it isn't culture if it's not cultivated from something specific to a particular place, I think creating with a connection to a given region can be very fascinating.

Finding nature hidden in the city dominated by humans

Tohoku culture is derived in relation to nature. But in areas such as cities where humans dominate, urban planning tends to result in similar areas devoid of character. For example, Roppongi and Shinjuku were originally separate areas and must have had different cultures and lifestyles. Although it's not easy to spot today, I imagine there must be some elements that are more or less rooted in nature, even in the ultra-urban city of Roppongi. In that sense, I think it would be interesting to have a research project where you walk around Roppongi in search of the things there that have always existed. That would change the way you look at the city, and I think it would be exciting to actually discover elements that are still rooted in nature.

Another thing. If the location is Roppongi, I would want to make some field recordings. It's a method that's common in music-making, where you record sounds such as from the ocean or the mountains and incorporate them into music. When you go into the city intending to record sound, your hearing becomes a lot more sensitive, which is something I experienced in the past. Your perception of the places you've walked through before changes completely as you discover entirely new sounds or noises you never noticed before. It may sound like I'm exaggerating, but I really felt a change in the way I see the world.

I thought that sensation could potentially be experienced in the three-dimensional world as well, which resulted in a past Self-Driven Research project called «Field Recording». I began by going out in the city with a 3D hand scanner instead of an audio recorder and took scans of various shapes. Then I edited those shapes using 3D CAD software to create objects. The idea of using the whole of Roppongi as material is very intriguing.

Field Recording

This Self-Driven Research project used a 3D hand scanner to impulsively collect scans of various shapes found in the city of Shibuya, which were then imported to a 3D CAD program and edited to create physical products. It was shown at Japon-Japonismes. Objets inspirés, 1867-2018, an exhibition that presented Japanese crafts and design in Paris at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Photo:Masayuki Hayashi

The importance of this project is to realize that there is no "correct" answer in terms of what sounds nice, or which shape seems interesting. You choose whatever thing from the outside world that inspires and seems intriguing. I believe the point is in the experience itself, of the overall process removed from logic and the act of reflecting on your senses to shape physical forms.

Materializing designs that evoke ideas in society

In encountering all kinds of things in everyday life, there are many moments I realize that I don't really know anything. Inevitably, not understanding hinders possibilities. In that sense there is so much I learn through work for clients. I dig deeper into those things through my Self-Driven Research projects, then funnel what I discover back into client work. That cycle is very important to me.

I also think it's meaningful to shape what I learn into physical designs. I sometimes feel like nowadays, design is described in terms that are too intellectual, but eventually, design loses a large part of its significance unless you get to the point of physical output. I've come full circle and now feel a strong need to make sure the design actually materializes in the end.

There are many things in this world that I wish were different. It's also true that it's very hard to actually make changes happen. To do anything new, you need to take all of the influence and convenience of technology that's been established and toss it aside, which isn't an easy thing to do. We may just be a small design studio in that big picture, but I still want to really think about what we're doing and use design to evoke alternative ideas in society. I hope that might lead to new values for a new future.

Photos taken at:THE MODULE roppongi『Cultural Synthesis in "THE MODULE roppongi"』(Friday, October 8 to Sunday, December 26, 2021)

Editor's Thoughts

Yoshiizumi-san's genuine impulse to "want to know," which also seems to be the driving force behind his work, isn't just about curiosity. He has an underlying respect for all kinds of things, be it people, things, nature, or culture. What struck me about his attitude is that although he is a creator of things, he also constantly thinks about living life through a design filter and contemplates how to make the world a richer place. He also has a gentle open-mindedness towards diverse cultures and ways of thinking, as well as the ability to take interest in a wide variety of things. That is probably why the things he creates are beautiful and memorable. I can only hope that he continues to make sure his designs always take physical shape in the end.(akiko miyaura)

RANKING

ALL

CATEGORY