INTERVIEW

108

Takeshi YoroAnatomist

Don’t Remove Unknown ‘Nature’; Study It

The art that sits at the border of senses and the physical world stimulates the introvert brain.

Takeshi Yoro is an anatomist who is known for his extraordinary affinity for insects. He is the exhibition supervisor for the current exhibition at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, “Insects: Models for Design.” He unfolds the amusing aspects of insect-watching and questions the capabilities of our thoughts and behaviors associated with insect-watching. Yoro, Japan’s mentor of knowledge, talks about the history of his love for insects, the lessons we must learn from insects, the charms of cities, and the future of Roppongi.

Insects are our precursors; Insects were here before humans.

People often ask me what I have learned from insects. But I think the order is wrong in this situation. My life began with catching insects, fish and crabs, so they have always been in my life. The world involving people is like an added relationship that came after my life of catching insects. It is almost like 'a societal duty.'

I was born and raised in Kamakura. World War II ended when I was in second grade. The kids back in my days had no adult supervision and roamed around freely. When I was growing up, Kamakura was full of vibrant undeveloped woodland, people were using charcoal, loads were pulled by cows and horses, and family doctors were traveling in rickshaws to the patients' houses. Back then, children had nothing to do but to catch insects. Many assume that catching insects was the activity I enjoyed solely during my childhood, but it has consistently been the core of my life even until now. When I am alone, I spend all my time observing insects or fish. In fact, I was out catching insects this morning.

I feel at ease when I am interacting with insects. The human world is too complicated. We have to worry about money and relationships with others, but these things do not exist in the insect world. I feel that my life is strongly tied to relationships with insects and nature. Insects have been on this earth some billions of years before we even existed.

When something remains 'unchanged,' it gives me a sense of comfort. The same goes for anatomy. When we are alive, we are continually moving. But when we are dead, we do not move nor change. Today's generations of people tend to complain about their anxiety, and it makes me wonder how they manage it. For me, in particular, my anxiety goes away when I am watching or dissecting insects.

Magnifying small objects means magnifying the world.

A leg of a Shiro-mon kumo zou-mushi (weevil) is magnified to 700 times of the life-size and displayed at 'Insects: Models for Design.' I often say magnifying small objects means magnifying the world. People have the inclination to assume that this magnification provides them a better perspective of the world. However, that is not the case. When small objects are magnified and the world is magnified, the world becomes blurry. As a specific segment is magnified at 10 times the original size, the segment surrounding it, the segment surrounding the segment that is surrounding the magnified segment, and the rest of the world are enlarged at 10-times magnification. The world at that magnification is too large for anyone to see. The world at10-times magnification entails there are 10-times as many things we cannot see. It only creates more things that are 'unknown.'

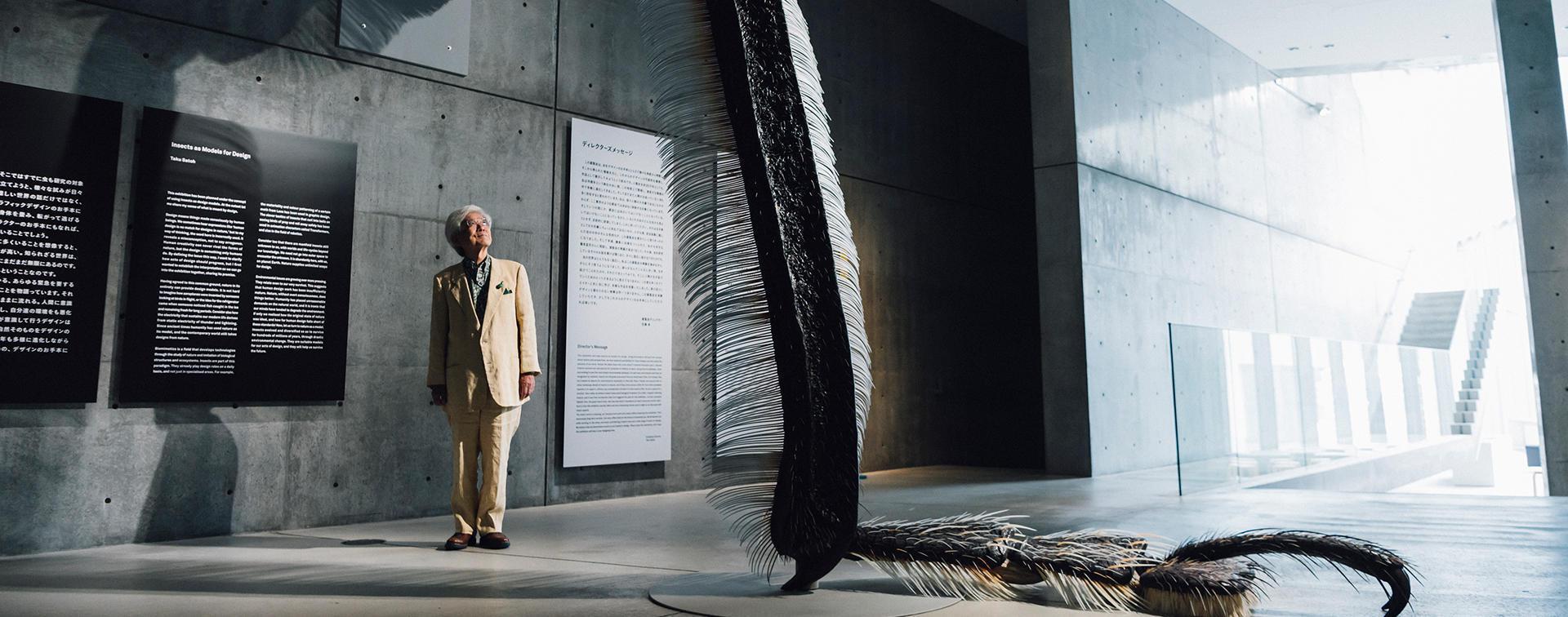

"Insects: Models for Design"

The exhibition opened with a graphic designer, Taku Satoh, as the exhibition director and Takeshi Yoro as the exhibition supervisor. A group of designers, architects and artists, who are inspired by many facets of insects, go deeper into designs through their work.

Dates: July 19 (Fri), 2019 to November 4 (Mon), 2019

Venue: 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT

Photo: Gallery 2

Photographer: Satoshi Asakawa

A magnification of a weevil leg to 700 times leads us to wonder what a sipalinus gigas' leg looks like. There are 1,600 different families of weevils. The complacency that you now know everything after seeing a segment of one type of weevils comes from the lack of observation. People jump to the conclusion that insects are all the same and do not pay attention to differences. They think, 'if a leg of weevil looks one way, a leg of a sipalinus gigas must look the same.' They would be amazed to know how different each insect is.

Weevil Leg

The most eye-catching exhibit at the venue is the gigantic insect leg; a left middle leg of a weevil is replicated based on 3DCG images and the precision photos by Kenji Kohiyama. The magnified replica at the 700 times the life-size enables the visitors to examine each strand of its fine hair. The art is created by a graphic designer, Taku Satoh.

"Weevil Leg" by Taku Satoh (Photographer: Satoshi Asakawa)

This is one of the reasons why I am so apprehensive about everything that is referred to as "progressive." When viewing human cells at 100,000 times magnification through an electron microscope, the actual human proportionately enlarges as 100,000 times as big. Studying everything about the cells at that scale is beyond what we are capable to do at the desk, and doing so is like traveling into the outer space. Similar practices are commonly observed in science classes. The professors and their students are convinced that they are facilitating the process of understanding the universe. Same thing can be said about this exhibition; no one should draw a conclusion that seeing magnified insects equals understanding the life of insects. This process of magnification only opens the doors to the "unknown."

"Unknown" doesn't mean a bad thing.

Having something that is "unknown" is not actually a bad thing. We can always turn that feeling of "unknown" into the feeling of "curiosity." We, humans, occasionally assume that having something "unknown" is a disadvantage to us and eliminate it when we are inconvenienced by it. Consequently, we decide to surround ourselves solely with the things that are "known" to us and the things with which we are familiar. In other word, we choose not to surround ourselves with the inconvenient and unknown "nature."

Humans possess aspects of nature since that is our origin. However, the cities are trying to eradicate those aspects from us. Those innate natural behaviors are often frowned upon in today's society and in the modern cities. If we, for example, urinate by the side of the road, we will most likely get reprimanded. The urge to urinate is instinctively natural, but our society and cities want to entirely eliminate what is intuitive to us. Another example is a random corpse. It can be startling. Death is a part of nature, and a corpse is a result of a death. But we wouldn't know what to do if we find a random corpse. What do we need to take care of the body, as no one knows what to do? The answer is easy; treat it like we treat an unconscious intoxicated individual. We don't purposely kick the intoxicated individual's head, do we? We simply transport the corpse the same gentle way we treat them.

What would be the end result if humans continue to eliminate what is natural to us? The brain will hide itself in consciousness, and that is exactly what we have today; the modern brains are "introverted."

Arts free the introverted brains.

One must regain the senses to recalibrate the "introverted" brain. Interacting with nature can bring back those senses, but an introverted brain may be overwhelmed. If it is suddenly exposed to a corpse or an intrusion of cockroaches, it will certainly shut down. Introducing the introverted brain to the beauty as the first step is a proper approach since the input passage must be opened to let the senses flow through. Given that theory, art is the ideal passage opener. It vitalizes the senses that connect to the outer world. Some art can be introverted, and our approach for this exhibition to use the nature theme of insects as the models for art and designs is going to be quite effective.

From the perspective of art being "man-made," we tend to use art as an antonym for nature. But it should not be used that way. Art, just like nature, sits on the borders of different senses; more precisely, it belongs to where the senses and the outer world meet. One of the exhibits "Caddisfly Nest" by Kenji Kohiyama is a set of graphic images demonstrating nature's creations through the artistic viewpoint. The nests that Caddisfly larvae construct with fallen leaves, twigs and pebbles are mesmerizing. However, how do we determine who the artist is? From the artistic perspective, is Kohiyama the artist or are the caddisflies the artists? How do we really know?

When we use nature as the models for our designs, it is up to the designers to decide how they want to unfold the nature. Occasionally, people ask me which books I recommend so they can learn about designs and nature. But books are nothing but outputs of human knowledge. Books are there to organize our knowledge, and experiences must be gained from the action. Taking the shortcut by reading about someone else's experiences is for lazy people. Physical labor, more precisely, using senses is what is crucial for creators.

Caddisfly Nests

The nests that caddisfly larvae construct underwater with fallen leaves, twigs, sands and pebbles are photographed as art. Different caddisfly families use different materials, and even among the same caddisfly family, their environments influence the variety of the nests. The exhibit showcases the diversity of nests and produces a visually pleasing sensation.

"Caddisfly Nests" by Kenji Kohiyama (photographer: Satoshi Asakawa)

New version of Kacho-Fugetsu. Humans need to stop taking credit.

Songs and picture scrolls have focused on scenery and objects from nature since the old days in Japan. However, more of them should incorporate what we are familiar with: insects. Kacho-FugetsuI means the beauties of nature and the first two syllables are written as "flowers and birds" in kanji. But where is the kanji for insects? I understand that people were bothered by the flies, and the insects were not considered elegant in the past. But the time has changed, and the kanji for cho in kacho-fugetsu should be changed from the one for "birds" to "butterflies" as they are homophones.

"Shape" is another aspect that makes insects rather amusing. Taking machines as an example, we humans accurately draft layouts to decide on the designs of the handle, the finish of the corners, and other details. But insects do everything on their own. In logic, the designs that insects create are in their genes, and those that humans create are in our brains. But I will not elaborate on how the brains are made of genes. In short, both insects and humans consequently produce incredibly identical things.

Fossils of trilobite's lenses are occasionally dug up. The cross-section of those lenses proves these compound eyes remarkably exceptional and identical to the lens used for gastroscope. Surprisingly, trilobites already had these lenses some hundred millions of years ago. Planthoppers have interlocking gears in their legs. The gear structure in their leg joints help the larvae jump, and the same mechanism is utilized for mechanical gears. We, humans, are conceited to think that WE are the inventors. However, we need to stop taking credit. While the connection between our abilities to create and the brain or body is still studied, we know that we are trapped in our own brains. To expand our potential based on the limitations we have, we should watch and learn from creatures other than humans.

Learn from nature, and assemble the life as an ecosystem.

Bio-mimicry has become a more commonly used word in recent years. I feel that our lives will improve if creators and manufacturers incorporate bio-mimicry in what they do. But we need to note that bio-mimicry does not merely mean learning from creatures or mimicking their functions and designs. It means that what we create must be incorporated and assembled well into the ecosystem. When we look at the process of how we dispose of broken items as garbage. In the ecosystem, there is a disposal cycle where insects clean up cow or horse feces before they are consumed by the next creatures in the cycle. The same streamline should be established for industrial manufacturing and social designing. Without it, we will keep creating garbage, and the trash keeps accumulating. We must learn from nature and assemble our life as an ecosystem.

Have you noticed how hideous solar panels look? I cannot understand why the solar panels are not designed after something aesthetically pleasant like leaves as they are utilizing the solar light. It makes me doubt the designers' intuition for having to opt for that product design. I often go to mountains to catch insects, and I am astounded by the sight of solar panels, covering the land where the trees used to soar. Allowing something that appalling will certainly plague our aesthetic sense. Wind power generators tend to stand in the way of beautiful scenery and need to be erected in less prominent places.

I think we, humans, have become more arrogant, and we can benefit from bio-mimicry, to live like other creatures. Insects are very modest. They have tiny bodies and miniature brains, but they are really "thinking." On the other hand, we have a brain that weighs over 1kg, but it feels as if we are using only a fraction of it.

Roppongi is geographically captivating. So let it be.

I hardly ever come to Roppongi, but I find it to be a captivating city. I like their undulating hills. The hills in Roppongi, as well as in Azabu, are fairly steep, and I consider Roppongi one of the geographically interesting places in Tokyo. Since I walk a lot on steep hills to catch insects, I am keen on this type of landscape. Flat, monotonous landscape in Tokyo does not interest me at all. When walking through streets on flat grounds, one wrong turn can get me lost completely.

Areas around Roppongi Hills have moderately steep hills. Before the areas underwent redevelopment, we could find bits and pieces of old Tokyo in those areas. They looked busy and hectic as if the time had stopped and we were stuck in post-war Japan. I liked it quite a bit. Roppongi Hills may be in retaliation to that. Everywhere we turn, everything is sparkly white today. Let's pick the hospital as an example. I understand it looks hygienic, but my concern is that being surrounded by nothing but white walls can aggravate the symptoms of the patients and elderly people.

I understand one of the objectives is to turn Roppongi into a uniquely attractive city. The problem here is that cities have the tendency to grow identical to each other, and that is inevitable. "Being identical" is the standard for cities. City developers try to make unnecessary changes and incorporate new ideas because they want their cities to be unique. But this is causing the cities to "be identical" and being identical has become the standard. So again, being unique is causing the city developers to attempt to change the city elements further. Only when the uniqueness is the result of natural evolution, it is considered genuinely unique. When these differences are created forcefully and intentionally, they are not the same as being unique. Each city has different demographics and will evolve on its own and become unique. So let Roppongi be. Its intriguing landscape will work its magic.

Cities need ambiance, and creators need good eyes.

Historically inhabited cities, like Kyoto, make me feel at ease. Kamakura, just like Kyoto, attracts people. It must be the city's charm. Having been born and raised in Kamakura, I really have to think about what makes Kamakura so special. I assume the city's religious background might be the reason that younger generations are allured to the city.

People today are agnostic; some religious beliefs have been embedded in our lives for centuries. As a consequence, we tend to choose places that are underlined by religions or where we can sense the religions. This is why Kamakura is so popular; the city is packed with temples and shrines. When I say religions, I am not referring to those that have long been practiced with faith and not those that are new or eccentric. People are attracted to the cities when there is a lingering sense of religion. The cities must have the "ambiance." Roppongi should leverage the presence of temples. This way, the temples in Japan can focus on their religious practice rather than their real estate business.

Earlier I talked about how crucial the physical labor and applying senses are. Let's take Roppongi as an example. We should see many things when strolling through the streets of Roppongi unless we are visually impaired. I am being serious, and this is an important point. To be able to see the world, we need eyes. We often do not realize that the reason we cannot see is because of our poor vision. On one TV program, the audience was astonished by the 20/4 vision of an African individual living in Japan. But that individual was frustrated and claimed that the 20/4 was not abnormal, and it was our vision that was considered abnormal and poor. Living in big cities have degenerated our vision and made us forget what is deemed to be usual among animals and insects. It makes me wonder what the underlying problems are...

Editor's Thoughts

Mr. Takeshi Yoro and I met on the pre-opening day of the "Insects" exhibition for which he worked as an event supervisor. He elaborated on his unique views that he gained through his own experience in a jaunty and rather incisive way. To back up his own comment, "to be able to see the world, we need eyes," he purchased a pair of opera glasses for this exhibition to scrutinize each art. The image of him studying and enjoying the insects derived art and designs made him look like a boy. On the side note, the name of the venue, 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, implies the importance of good visions and the ability to look. It does not matter if it is the potential of the city or the potential of our thoughts and actions, I have learned that everything begins with the action of looking. (Text by Tami Okano)

RANKING

ALL

CATEGORY