Shared understanding beyond nationality or gender

Connecting Japan to the world to create freedom without borders

Chiharu Shiota currently has a major solo exhibition on at the Mori Art Museum that spans 25 years of her work as a contemporary artist. Her works express the intangible—life and death, concern, anxiety—things that are emotionally perceptible but never physically visible. Although her inspiration comes from her own personal experiences, her works attract and resonate with so many people because of their underlying universal themes. We interviewed her from multiple angles, including her thoughts on the exhibition, her current life in Berlin, and differences compared to Tokyo.

A discovery made by digging deep inside for the largest solo exhibition to date.

Just before this interview, I actually went to the Mori Art Museum and took a peek at the Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles exhibition. There really were so many people there, which was quite a surprise. There's no one there when I'm actually working on a piece, so seeing people present next to my artwork was a very curious thing to see.

The very first installation you see when going in is Uncertain Journey, where I saw a person look very surprised upon entering the room and another person looking just as surprised next to them. They were obviously strangers, but the next instant they made eye contact and shared a moment of silent acknowledgement, which made me very happy.

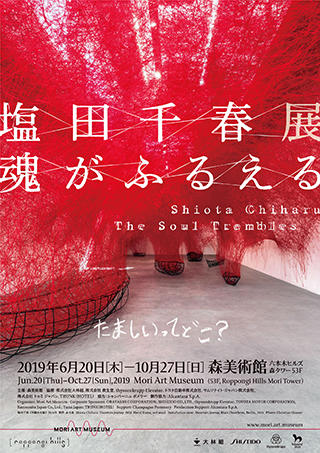

Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles

The largest-ever solo exhibition by Shiota Chiharu with a comprehensive look at 25 years of her oeuvre. Primarily consisting of new and previous installations, the exhibition also includes sculptural works, performance video footage, photographs, drawings, stage design-related material, and more, greeting visitors with fundamental questions about the meaning of life and the concept of the soul.

On at the Mori Art Museum from Thursday, June 20 to Sunday, October 27, 2019.

Uncertain Journey (2016, 2019)

An installation of boats arranged in a room with red string strung all across. The length of red string apparently comes to an amazing total of 280 kilometers. Boats are a regular motif in Shiota's works, but instead of using actual boats like in previous exhibitions, this installation features more abstract forms that only suggest their framework.

Courtesy: Blain|Southern, London/Berlin/New York

Exhibition: Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles, Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), 2019

Photo:Sunhi Mang

Image source:Mori Art Museum

I've had opportunities to compile my artwork before, but I don't think I've ever dug as deep inside of myself as I did for this exhibition. Each and every exhibition felt like a separate challenge at the time, but gathering all of my works together like this made me reconfirm that my past is linked to the present.

For example, one of my earliest works was a performance piece where I dumped red paint on myself to "become" a painting, and another was an installation using red thread, which made me realize that even back then, red was my color of choice. I didn't really think about it at the time, but red is still an important color in my work today. When I saw that the color had been there from the very start, I was reminded of how my art is all tied together.

Dirt was another common link, like the footage of my performance rolling around naked in the dirt followed by the muddy dress, and then the performance where I used showers to wash the mud away. But the video of me pouring mud on myself in a bathroom brings back all the distress from that time, and I can't bring myself to watch it now. The performance came out of what was going on in Berlin at the time, so I feel a certain sense of separation from it, and if I were to experience the same kind of distress now, I feel like I would express it in a completely different way.

An exhibition born out of a struggle with disease. How I defined who I was by putting my thoughts into art.

This exhibition came about in a very unexpected way. Chief Curator Mami Kataoka contacted me and we met in Berlin. It happened to be the night before I was scheduled to have surgery, and when she proposed this solo exhibition, I felt so lucky to be alive and so glad that I had kept up my art for this long. Then the next day, the doctor told me after the surgery that the cancer was back.

They initially thought it was going to be an easy procedure, but when they opened me up the cancer had spread more than they had anticipated, and I had to have three organs removed. Once that major operation was done and the chemotherapy started, I was whisked through the various stages of treatment as if I were on a conveyor belt. Even though I knew that I would get better as long as I stayed on that conveyor belt, I felt that the feeling, conscious part of me that made me who I was had gone missing. All I had left was the feeling that my soul had been left behind.

From that experience, I wanted more than ever to create work that touched on emotions and consciousness, to give form to what was otherwise intangible. My illness had an impact on this exhibition in many ways. Where do emotions and consciousness go when life ends? If the body is only a shell, then where would the inner part of me go? And if worst comes to worst, how would my daughter live on without her mother? Those are the questions and anxieties I faced when planning this exhibition.

The human soul can't be solved that easily. That's why it's creative.

The tagline "Where is the soul?" that appears on the key visual was written by my daughter, who is turning twelve. Just as the words say, I think the human soul is the most unfathomable thing of all. Emotions change all the time. Sometimes people hate because of love. It's all very complicated, and I think everyone goes through life overwhelmed by conflicting emotions.

If I didn't have a soul, I may have never felt that the chemotherapy had left my soul behind, or that I had lost what made me who I was. I think I would have been much more okay with the treatment, and things would have been much more simple. But the reality is that I do have a soul, and because I don't know how to explain it, that's what leads to expression.

I feel like this exhibition has given me a better understanding of who "Chiharu Shiota" is. It's been a while now since its opening, so my work here is pretty much done, from here on out, I hope that my works live on in the memories of the people who come to see them.

Everything is lacking in some way. Making art is the act of filling in what's missing.

This is different from when I felt a part of me was lost during the treatment, but I have always felt a sense of "deficiency." Everything about me is lacking in some way, and the way I fill those voids is to make art. That's why most of my work is inspired by some small deficiency or discrepancy.

After about three years living in Germany, I came back to Japan for the first time in a while and all kinds of things felt unfamiliar. My old shoes felt strange and uncomfortable even though my feet were the same size. Something didn't feel right when I met with old friends. The people, the things, the scenery... Everything felt off, and there was a gap between the Japan I actually saw and the Japan I had envisioned during my three years away. The question of "why" translated into my art.

In my case though, these inspirations don't immediately become art. There's an incubation period where I examine what I felt and really develop that idea before ultimately giving it form. Even if a new idea comes up during that process, I never make sketches. Because the moment I make a drawing of it, I've created something, and that becomes art. Instead, I sometimes jot it down in words. For example, my work "In Silence" that features a burnt piano started with me writing down "my true voice is silent," and I developed the idea from there.

In Silence (2002, 2019)

An installation with a burnt piano and seats tangled up and enveloped in a mass of black thread. Inspiration also came from Shiota's childhood memory of a next-door house going up in flames in the middle of the night. The soundless piano symbolizes silence, and yet has visual music emanating from it. At once overpowering and evocative of the delicate nature of the soul.

Production support: Alcantara S.p.A.

Courtesy:Kenji Taki Gallery, Nagoya/Tokyo

Exhibition:Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles, Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), 2019

Photo:Sunhi Mang

Image source:Mori Art Museum

However, the image I have in my head starts to disintegrate when I set off to find materials. I never know if I've chosen the right material, whether it's really what I imagined...and it results in so much doubt and confusion. That's the toughest part of the process. It then often takes a very long time before I feel like something is truly finished.

For example for "Accumulation - Searching for the Destination" , I initially got about ten suitcases together, which wasn't nearly enough. I collected more and put them in an exhibition when I had 200, but I still felt that wasn't enough and ultimately got together about 440. I keep tweaking my work through exhibitions in various countries until I'm satisfied, and that's the way I create things. "Accumulation" is a perfect example that transformed its way through its iterations in Serbia, Italy, Denmark, and Japan on its gradual process towards completion.

Accumulation ― Searching for the Destination (2014, 2019)

A myriad of suitcases ― ultimately coming to a total of 440 according to the interview ― float in the gallery. This installation was inspired by Shiota's discovery of some old newspapers in a suitcase she found at a flea market in Berlin. The suitcases swaying and banging into each other make them seem almost animate, giving the impression that the memories and journeys of their unidentified owners still continue on.

Courtesy: Galerie Templon, Paris/Brussels

Exhibition:Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles, Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), 2019

Photo:Keizo Kioku

Image source:Mori Art Museum

Having free time to do nothing and be unproductive is the most valuable thing of all.

In the creative process, I feel that having free time is particularly important. With the café culture in Europe, I see lots of people doing who-knows-what sitting in cafés and drinking tea in the middle of the day (laughs).

Having free time to do nothing and be unproductive, where you just sit and stare off into space, is incredibly important. For example, whenever I stop by a café on the way to work in the morning, I start off thinking about all the things I have to do, but once I get past that and manage to space out, all kinds of thoughts and ideas about my art start popping into my head. If anything, there are things that only emerge during those times. In making art, having time to do nothing is indispensable for me.

Berlin, a city with incredible energy and magnetism.

I currently live in Berlin, but I didn't start off thinking I would live there. After graduating from art college, I found that it was practically impossible to hold solo gallery exhibitions or have your work shown in museums straight away, so I considered going aboard to further my studies. There was a place accepting students in Germany at the time, and Berlin was so appealing when I happened to visit that I started living here.

The Berlin Wall that split East and West Germany came down in 1989. I moved to Germany a few years after that, so there was construction going on everywhere and artists were flocking in. Freedom was in the air, and back then if there was an exhibition, biennale, or triennale happening somewhere in the world, it was sure to be filled with artists from Berlin. Artists from all over the world had their studios in Berlin, with a diverse range of nationalities mingling and asserting their creativity. There was incredible energy and magnetism there.

The Berlin Wall

Germany was split into east and west after World War II, and there was economic disparity between capitalist West Germany and socialist East Germany. People were constantly defecting from East Germany to the west, and the Berlin Wall was put up in 1961 to prevent those escapes. It remained there for 27 years until 1989, when it was taken down before East and West Germany were reunited a year later. Part of the wall is preserved to this day as a cultural property, covered in murals by over 100 artists.

That atmosphere made realize that I definitely wanted to live there. Thinking back, I think I was there at a very special time. All kinds of people and cultures were pouring in, and the air was filled with the promise that something was about to be born, kind of like New York in the 70's.

Berlin is all spruced up now and has a different feel to it, but one thing hasn't changed: it doesn't feel like Germany although it's in Germany. With its multinational population, the people there look somehow different from those in Munich or Frankfurt. Maybe that's why I forget my own nationality when I'm in Berlin.

The harsh contemporary art scene in Japan that I experienced in my twenties.

That sense of freedom is what gave birth to a lot of my works. I think if I had lived in Tokyo for a lot longer, I would never be making the kind of art I do now. One time when I was 22 or 23, I went around the galleries in Ginza with my portfolio stuffed in my backpack, hoping to hold a solo exhibition. Naturally, the response was harsh. First of all, you need a whopping 500,000 yen to rent a gallery for one week. Even if you somehow scrounge up the money, the only people who would come are your friends and teachers from art college. There's no point in doing that.

The concept of rental galleries doesn't exist overseas to begin with. People hold exhibitions and operate off of the sales. But in Japanese galleries, not only does the artist have to pay to rent the space, the gallery takes an additional margin of the sales, making it prohibitive for students and young artists. This system was standard practice 20-or-so years ago. There was very little appreciation for contemporary art as it was, and making a living as an artists wasn't feasible. Nowadays, people kind of understand when I tell them that I'm an artist, but I still get asked what my "real" job is ― how I pay my bills ― at least once (laughs).

It's not easy making a living as an artist in Germany either, but I think the difference compared to Japan is that art is a part of everyday life. People buy contemporary art as Christmas presents, and very casually have art in their homes. Above all, the people there have respect for artists.

The joy of decorating the house with favorite paintings over "inconsequential" material wealth

Of course, Tokyo has changed since then, too. I feel like art is slowly taking root and becoming a part of life here. But whenever I visit, I do feel that some aspects of society here are very competitive. Not in terms of talent, but material issues ― where you live, how much money you have, where your child goes to school...things like that. I can't help but feel that Tokyo is overrun by "inconsequential" things that you can't take with you when you die. And I think that leads to people sacrificing their health trying too hard, or not being able to express their feelings very well.

Materially speaking, Berlin's subway is so old that it feels like it's from the 70's, and people generally don't care about fashion. But that's not a problem when you live there. More importantly, you might decorate your home with a favorite painting or something that can spark a conversation and a connection. That kind of thing has much more priority.

I think that might be largely due to the difference in education. In Japan, you're expected to say the same thing as everyone else, but in Germany, you're expected to say something unique. But I think Japan is still changing. People can have different feelings, have different opinions, clash, and create something together as a result. I think that's much nicer and more human.

Although a part of Asia, Japan is Japan.

The art scene in Japan is changing by the day. For example, Japan no longer has to boost its status by always hosting exhibitions from Europe or America. Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles is scheduled to tour through Busan, Brisbane, Jakarta, and Taipei, and it makes me very happy to see that now there's actually a demand for Japanese exhibitions to tour through Asia.

What's more, the world is focused on Asia now. Its sheer energy, speed, and how people act and think here are distinct from other regions. There has been a recent surge in Asian art collectors, and more and more museums are cropping up every day. Most major artists participate in Art Basel Hong Kong, and MoMA's collection meeting is also held in Hong Kong.

Art Basel Hong Kong

Art Basel is an annual art fair that has been held in Basel, Switzerland since 1970. The show is now held in Hong Kong and Miami in the United States as well. Art Basel Hong Kong is symbolic of the rapidly growing art market in Asia. Both big-name artists who are on the forefront of the global art scene and remarkably driven up-and-coming artists come together to show art in a diverse array of genres. This image is of Shiota's installation "Where Are We Going?" (2019) at the 2019 show.

Exhibition:Encounters, Art Basel Hong Kong 2019

Courtesy:Galerie Templon, Paris/Brussels

Photo:Sébastiano Pellion

Meanwhile, I do feel that Japan is getting pushed aside in this upsurge. For better or for worse, Japan has a lot of pride and gains respect from the other countries in Asia. So a lot of places in Asia are happy to put on exhibitions from Japan, but Japan itself doesn't think of itself as a part of Asia. My impression is that it exists separately from the rest of the region, on its own. Before I returned from Germany, I always thought Japan was a part of Asia, but I was wrong. Japan is Japan.

No borders, where nationality and gender doesn't matter. Contemporary art should be free.

Why should that kind of boundary exist? It's perplexing. The world of contemporary art should be free, and yet it's still constrained by borders and nationalism.

For example, I'll go to an exhibition on globalization and they'll detail how many countries they got artists from, listing the Japanese artists, African artists, American artists, and so on. That's a result of nationalism, isn't it? Then there was the time when I showed my work at the Japan Pavilion in the Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition, and was asked how I felt representing Japan, which didn't sit right with me.

Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition, Japan Pavilion

Shiota was selected to be featured in the Japan Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition held in 2015. She created a large-scale installation entitled "The Key in the Hand" (2015) that made use of the gallery on the second floor and the outdoor pilotis on the first floor. The installation stunned visitors by filling the space with strands of red yarn that had 50,000 keys hanging off the ends. Keys are precious items that protect the important people and spaces in our lives, and also serve to open doors to the unknown. The keys here are like the multilayered memories of the world, confronting viewers to think about the meaning of life.

Exhibition:56th Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition, Japan Pavilion (Italy), 2015

Photo:Sunhi Mang

I don't mean to reject Japan, of course. I just don't make art that depicts typical Japanese culture like ikebana (Japanese flower arrangement) and tea ceremonies. I strive to encourage shared understanding beyond nationality or gender, so I simply don't think of myself as representing Japan in the first place. I hope that we can eventually move towards a world where borders like that is less of an issue.

Excitement for the youthful energy in Asia and their enthusiasm to know more.

That's why when faced with making something here in Roppongi, I wanted to create something that connects Japan to the world, and does away with borders. As the first step in that, I wanted to show what Roppongi is like. The Mori Art Museum is unrivaled in the sense that, as far as I know, it's the only large museum in the world that exists so high up in the air. It's a thrill just imagining Mr. Mori's excitement when he thought about creating a museum 53 floors above ground level.

At the moment, art industry people around the world are really interested in the Mori Art Museum and Naoshima Island. People are very intrigued as to why the rural island has so much contemporary art, and why the elderly there know how to talk about the artwork. I would want to go beyond a superficial description and showcase those interesting aspects in a more candid, relatable way.

Personally, exhibitions in Asia are what interest me the most right now. I'll be meeting with some museum people in Hanoi and China soon, but a lot of them are in their twenties, which is very young. They're at that age where they're getting interested in contemporary art and just soaking everything up. It's really interesting talking with them, and I'm genuinely excited about the prospect of working with these kinds of people in the future.

Editor's thoughts

Shiota-san's works have powerful presence but also the subtlety to find their way into the viewer's soul. A proper look from the front versus a spontaneous glance back over the shoulder offers viewers with completely different perspectives. The fear for the unseen seems to coexist with hope in her works ― hope that exists precisely because things are unseen. After the interview in which she was meticulous, quiet, but very strong in her convictions, I couldn't help but silently thank her for being alive. The Soul Trembles is a product of her facing mortality, where she got a firsthand sense of what it means to be alive. I quietly look forward to see where this experience will take her next. (text_akiko miyamura)