INTERVIEW

102

méContemporary Art Team

Segmentalizing the work of artists will energize the art scene

What becomes visible when many viewers gather to see art

mé is a contemporary art team whose core members are contemporary artist Haruka Kojin, art director Kenji Minamigawa, and art installer Hirofumi Masui. The team’s simple and impactful name means “eye” in Japanese; the team puts a strong emphasis on turning our eyes to the uncertain reality around us and to phenomena which we are not usually aware of. Every time the team releases a work, it attracts much attention. In this interview, we asked Kojin and Minamigawa about their new work currently being shown at Mori Art Museum’s “Roppongi Crossing 2019: Connexions” exhibition, about the relationship between artwork and viewer, and about what becomes possible when the team is well-bonded.

The wish to see the scenery from eyes that are torn into bits and thrown in the air

MinamigawaThe work "Contact" being shown at the "Roppongi Crossing 2019: Connexions" exhibition originated from the sensibilities of Kojin who told me that she is not able to see scenery as she can't get close to the scenery itself. I thought that scenery is something that one ordinarily sees, but Kojin said, "When I approach a forest and get closer to it, what I see becomes a group of a trees, and then a tree, and then the leaves of tree, and so ultimately, what I see is not the scenery."

"Roppongi Crossing 2019: Connexions" exhibition

The Roppongi Crossing exhibition is held every three years at Mori Art Museum to "provide an overall snapshot of the state of the Japanese contemporary art scene." In its sixth year this year, the exhibition is displaying works by 25 Japanese artists and groups who were born in the 1970s-1980s. The exhibition focuses on the connections seen in contemporary expressions. Held Feb. 9 (Sat) - May 26 (Sun) 2019.

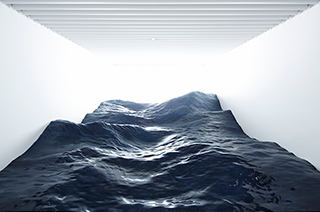

"Contact"

An installation which "looks like a scenery of the sea" and at the same time, can be perceived as a "nearby solid mass." In the beginning, there were plans to add details such as sea waves and floating garbage like plastic bottles. However, a decision was made not to inform the viewer of size and distance. Instead, the work was made to allow viewers to see the work as they liked.

"Roppongi Crossing 2019: Connexions" exhibition at Mori Art Museum in Tokyo.

Photograph by Keizo Kioku Courtesy of Mori Art Museum

In order to understand what Kojin wants to make visible, I always ask her a lot of questions. Listening to Kojin talk about not being able to get close to scenery, it became clear that she was thinking about how, for example, a flock of white-cheeked starlings flying in the sky sees the scenery. Instead of the perspective of one bird, Kojin is interested in seeing how hundreds and thousands of birds - as one aggregate of living creatures - would see the world - that's the perspective she's interested in. And as we kept thinking about this subject, Kojin said something like, "Maybe it is my own body which is hindering me because it gets closer or further from the scenery. I wish I could tear my eyes into bits and throw them in the air so that I can see the scenery from the air." The idea of looking at things in a way that goes beyond the perspective of a sole individual made us think anew about the art viewer's perspective.

This is a bit complicated, but flowers have color even though they have no eyes. Among people born without eyesight, there are some very fashionable people. There was a time when I pondered a lot about the reason. Flowers get information from butterflies, and give their petals their colors. I heard that blind people choose the clothes they wear by sensing the response from the people around them. You could say that they are "seeing" through other people. When I realized that we can see things even without physical eyesight, I felt there were amazing possibilities and I became very excited.

When we make a work, we see it many times in the atelier in its production process, and it is not possible for us to encounter our own completed work for the first time. I was once jolted to hear a member of the production staff say, "I am involved because I like mé's works, but I face a dilemma because I inevitably get to see the works during the production process." The staff works with the desire to see the completed work, but they never see the work for the first time. But just as flowers look at things though butterflies, I feel that mé is also trying to look at things through the general public who view our works.

When we made a work called Elemental Detection that is like an imaginary lake, we witnessed the vivid response of viewers. The visitors moved about much more freely than we imagined, and they responded in so many ways, and that is what led me to the idea [that things can be perceived through the eyes of art viewers].

"Elemental Detection"

A mystical installation that looks like a lake was placed in the grounds of an abandoned facility building. The work was released at Saitama Triennale 2016.

Saitama Triennale 2016, installed at the former Saitama Prefectural Culture Center

Photograph by Natsumi Kinugasa.

KojinWe carefully simulate the "dosen" (the walking route) which people will take to come and see our works. For example, we imagine a visitor coming to an art museum for the first time and we walk many times to a piece of work; we refine the work by imagining how the person would feel on glancing at it. The visitor's "dosen" is an integral part of our work.

MinamigawaThat's why we don't want to make presentations where a work seems to be suddenly thrust in front of people as if we are saying "Look at this!" But this time, with "Contact", the venue is an existing exhibition room in an art museum, and that means that visitors are essentially instructed to look within the room. So it's a way of presentation that is totally opposite to the way mé's works are usually presented. Once in the room, we want visitors to see what we call "scenery that cannot be seen."

KojinThe physical work itself is right in front of you, but I hope that what people see is scenery in the distance.

MinamigawaWe chose the sea as the motif because we thought that the sea is the best example of scenery that looks different depending on whether you look at it from a close distance or from afar. For instance, you might be driving in a car and see the sea faraway, and you think, "Ah, how beautiful." and you get the urge to go closer to it. But when you actually come nearer to it, you of course come to the beach, and the waves are clashing into the bare rocks and the sea spray is awesome, and things might not be as pretty as you expected. Nonetheless, I used to think that I was seeing the sea up close. But when you think of it in the way Kojin thinks, you could say that all I was seeing were the physical waves, the sea spray, and the seawater, and that I never got close to the scenery of the sea I saw from the car.

The title "Contact (Keitai in Japanese)" (The kanji character "kei" means scenery while "tai" means physical) signifies something we cannot see, something that is midway between scenery and a physical thing. I sometimes observe the visitors at the exhibition venue. Once, there was a person who looked at our work and said, "I feel as if I could fall into this" and a person who kept gazing at a work for a long time. There was also a person who looked at a work only for a moment and walked away, and another who was unimpressed, saying "This is just a fake thing." Their responses are neither good nor bad; it's as if I am looking at the whole range of how people look at things. And it is not only us, the creators, who are affected by observing the viewers; I think a relationship is formed among the viewers themselves and that they gain information from one another. For example, if there is a person looking intently at a work, other people will be drawn to look closely at it too, and children will pull their parents' hands and come back for another look. In contrast, if there is someone who quickly walks away, there will be people doing the same thing for some time. On social media, interpretation about a work will gradually emerge and the response of the viewers will then change.

There is something that becomes visible when many viewers gather to see art. When we were making plans for "Contact", we were in fact afraid of creating something that would make people think, "It's trite" or "It's just an artificial sea." But we released the work, deciding to take up the challenge once more of having lots of people look at something - for it is their response that paves the way for new possibilities; now we are prepared for all kinds of responses, including the kind we were initially afraid of.

Understanding each other is vital in creating our works

MinamigawaOur usual procedure in making works is for Kojin to first come up with an idea, and then for me to keep asking her questions about it. With the "Contact" for instance, it began with Kojin's comment that she can't get close to the scenery. When I asked her what exactly that meant, she said she wished she could tear her eyes into bits and throw them in the air - and so began a difficult-to-understand conversation which sometimes made me become increasingly annoyed. (laughs)

KojinSometimes, he asks questions rather sharply and so I become a bit irritated too. (laughs) But when I felt I've failed to communicate, I took him to a large car park and asked him to lie down on a chair in different places. I said "Lie down on your back and look at this sky!" and tried to make him understand through his physical senses. The people around us must have thought we were weird. (laughs)

MinamigawaAnd then we turn the idea into a specific plan, and convey it to Masui who is in charge of overall production. Then Masui pours much passion into making samples, and we discuss things over again and make improvements. For "Contact", Masui made a considerable number of samples.

KojinWe talked for a long time about why the sample didn't look like the sea I had in mind. If one wrong decision is made, the work would become a totally different thing, so we need to be in true communication with one other and know what parts of a work to eliminate and what parts to enhance. We feel worried until we are certain that we understand each other. Understanding is the key; there is a moment when all of us know which parts are good and which are not. When we reach that point, things can suddenly begin to proceed very smoothly.

MinamigawaMaking our recent work, there were times when I felt it was really fascinating, while at other times, it seemed dull. I realized that feelings can change even when looking at the same thing, and that we were trying to express in our work an idea that we ourselves could not fully grasp. Until I came to that realization, I felt unsure and kept asking Kojin, "What was the thing you were talking about at the very beginning?" The work was created by around 10 people; Masui was very attentive about keeping the team bonded. For the latest project, we asked a young art installer called Tomohito Hiratsuka to be chief of the production team; Masui focused on having good teamwork so that Hiratsuka could make the best possible decisions and make the most of his artistic sensibilities.

The rule to tell each other all the negative feelings bottled up inside

MinamigawaTo make sure that the three of us understand each other, we hold what we call a "mental meeting" about twice a month. This is because even though we have been working together for six years, there are times when there are misunderstandings; as production of the artwork enters its vital stage, the emails we send can become blunt and the recipient can become unnecessarily worried, thinking, "Did I do something wrong?" So we have set up a strict rule to be open about negative feelings bottled up inside. It's embarrassing to do this as grownups, but we ask questions like, "What were you thinking when you sent that mail?" and sometimes the conversations can become tearful. (laughs) But unless we are able to smile and make a high-five at the very end, both the production of artwork and our relationship become awry.

KojinThere are times when work becomes uninteresting and stagnates over really trivial matters. For example, when a lot of garbage piles up in the workplace, someone might feel that the other person is insensitive about garbage and that can lead to all sorts of needless speculation. But for the six years we've worked together, we've been telling each other the bothering thoughts that come to us, and we've found out that most of our thoughts are wrong assumptions or misconceptions.

MinamigawaAt the mental meetings, one is revealed to be a small person and it is embarrassing, but we need to hold the meetings in order to make good things. The most important thing is to simply and boldly express your feelings in order to understand each other. (laughs)

KojinNonetheless, when I see the word "mental" written down in the schedule, it still makes me feel down. (laughs)

The decision to quit being an artist in order to create good works

KojinSince childhood, I've been drawing sketches when something catches my attention in my everyday life, or when I think of something. I really enjoy freeing my imagination and coming up with ideas, but when it comes to thinking about the title of a work, or showing it to someone, my enthusiasm drops drastically. And when production starts, it becomes necessary to cooperate with all kinds of people to move things forward, and I'm not good at presiding over such projects.

Working as a team member of mé, I can concentrate on what I'm good at, and I'm grateful for that. Minamigawa translates the things that caught my attention into words and specific plans, and Masui makes the works; that process can lead to unexpected methods, and can totally change what I initially had in mind. Each of us can do our work because of the trust we have in each other, and I find that I can be myself more when I belong to a team.

MinamigawaI met Kojin at the Graduate School of Tokyo University of the Arts. Masui and I were doing a project called "wah document" where we reversed the artists' privileged rights, and collected ideas for artwork from the public to make them into reality. While we were doing that, Kojin was making works based on her memories of when she was a one-year-old, and I thought she must be a genuine artist. I found her talent appealing but I didn't want to admit it for some time. The motivation for my activities was the biased belief that I was doing something very unique, and I didn't want to accept the fact that it might not be so. There was a time when I telephoned my friends and kept asking, "I do have talent, don't I?" (laughs)

Then I began to think about what would happen if I admitted that Kojin has talent which far surpasses mine. It was then that I thought of forming a team where the members could specialize in their various areas of creativity. There are all types of artists - artists who excel in management and artists who are good at communicating with people, for example.

But with the current art university system, if you want to make artworks, the only option is to declare yourself an artist and to work accordingly; under this system, a considerable number of artists go out in the world every year. But if the creative work is segmentalized so that people could become art installers or coordinators or managers - doing what suits them best - it would lead to better activities and better forms of expression, and I am sure the art scene will become much more energized. At present, the number of active artists is larger than the number that is needed in society. Yet there is a large shortage of interesting works and new activities which are the most important things. So I decided to be realistic, and aim to be the first example of a team that would bring change to this stagnation.

wah document

An art project that Minamigawa and Masui undertook before launching mé. Ideas for artwork were collected from children and the general public, and the two created the works jointly with participants. Activities, which included playing golf on the river and lifting a house with human power, were undertaken all around Japan.

Life will become more fun if we set aside space to accept the unknown

MinamigawaI think it's interesting that there is a direct link between art and our views of life and death. I'm almost 40, and I sometimes wonder how much money I will need if I am to live another 40 or 50 years. And many other people probably ponder the same thing, and inevitably we all ask the question of "What is my life about?" (laughs) But it's essential to be positive about life, and I think art helps us to do that. There are things that we might lose sight of any moment, but I would like to flips those things over.

KojinLiving one's life is not easy, and there's a tendency to respond to things we can grasp and understand. But I think it's very important to be positive about the unknown and to accept the fact that we don't understand. When we are children, we absorb so many things that we don't know, but as soon as we understand something, we stop thinking about it and cease to see it. Yet there really is such a lot that we cannot know, and I feel that turning our attention to that affects our views on life and death which Minamigawa just mentioned. I feel that if we could set aside space in our everyday lives to accept the unknown, we will find life more fun.

Feeling the reality of art by seeing the responses of viewers

KojinRegarding our latest work "Contact", Minamigawa talked earlier about the response of viewers. There are people who seem to become aware of something and look surprised, people who suddenly start taking photos, and people who start talking about something totally unexpected; when I see viewers behave in their own individual ways, I too am sometimes taken by surprise, or feel that I share their views, and sometimes, I am so glad that tears come to my eyes. Such moments when I am moved and when something new is born, are very important for me, and recently, it is precisely in these moments that I can feel the reality of art.

MinamigawaIt is only through the viewers that creators can encounter their works.

KojinOn the subject of viewers' response, there is a story I heard which I like best. We floated a 15-meter-tall artwork called "The Day an Ojisan's Face Floated in the Sky", which as its title says, is a three-dimensional object bearing the face of a middle-aged man. Two middle-aged women saw this; I heard that they were walking from opposite ends of a bridge, and when they saw the face of the middle-aged man floating in sky, for some reason, they suddenly embraced each other, even though they were strangers, and then they both apparently wept tears.

"The Day an Ojisan's Face Floated in the Sky"

One of mé's most well-known works, this artwork is a huge three-dimensional object bearing the face of a middle-aged man - an image of a real person chosen from photographs sent in from the general public. The work was shown in 2014 as an outdoor project at Utsunomiya Museum of Art, and was floated in the sky for two days. Under a new project called "Masayume", a similar work is planned to be floated in Tokyo in 2020. mé is asking people from around the world of any nationality, age and gender to send in their photographs so that one face can be chosen for the work.

https://masayume.mouthplustwo.me/

Sponsored by the Tokyo metropolitan government and Arts Council Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture)

2013-2014 Outdoor project 2014 at Utsunomiya Museum of Art (Tochigi Prefecture)

MinamigawaThis is something we can talk about now, but for the work "Completed Conjecture", we used an empty space to make it look as if it had formerly been a coin laundry shop. As you would expect, a lot of visitors asked, "Was this place originally a coin laundry shop?" And a local middle-aged man apparently replied that it had indeed been a coin laundry shop in the past. We don't know how he came to have that belief, but it's interesting how misconceptions like that can spread and influence the way people look at artwork.

"Completed Conjecture"

An old shop facing a national road was remade to look like a coin laundry shop that had always operated there. The work was shown at Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale 2015, and visitors waited in lines to see it.

2015 Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale 2015 (Niigata Prefecture)

The walking route in Roppongi and how any kind of work will blend in

MinamigawaWith the Mori Art Museum, the visitor reaches the exhibition room after passing all kinds of advertisements, so the walking route is very unusual. If the same work was in an art museum outside of Tokyo, it would probably look totally different, but in Roppongi, people see numerous adverts such as garish movie posters and fashion adverts on huge monitors, and then they encounter the artwork, so I think that any kind of work would blend in with the environment, whether for good or bad. Maybe in Europe, where there is a mature culture and an established way of looking at works, things would be different. However in Japan, artists have the privilege of doing almost anything as long as it is economically viable, and in that aspect, Japan is probably the freest place in the world.

When you think of that, changing the streets may not be a very difficult thing; I think there is a lot that could be done. Roppongi is so strongly built, filled with buildings and looks like a place where no more improvements can be made, and yet there are still all kinds of people who still want to do something. I find it interesting that people think that way about Roppongi - I don't think there are many places like it.

Actually, I have an ambitious dream: I want to make create a traditional Japanese-style place somewhere in the streets. The architecture doesn't need to be made of real wood - it just needs to have a Japanese appearance. In fact, it would be better if it looks artificial. It would be like scenery that had abnormally developed in the Edo era, and I think it would look extremely weird and beautiful. Such a place would probably have the effect of making the expressways look cool. With a few touches, even the cold-looking high-rise buildings can be made to have the Japanese look. I'm good at that sort of thing, so I would be eager to make a cost estimate.

KojinI would like to create a space that is absolutely meaningless. I think it would be fun to have a sort of lawless area where people accept the fact that there is nothing there. During Halloween there was that raucous incident in Shibuya, but the people probably didn't intend to do bad things. I think they just wanted to share the sense of freedom with others, and feel a sense of togetherness in that moment. So I'm interested to know what kind of scene people will make if they were told that they were free to do what they liked in a certain place.

MinamigawaWhat interests me right now is the notion of "ku" that an acquaintance of mine who is a Buddhist monk, told me about. Apparently what exists is the same as nothing existing and I would like to know what that means. Kojin knows and says "When you close your eyes, the world does not exist" which is the same kind of thing the monk was saying. But maybe Kojin is only pretending she knows. (laughs)

KojinMinamigawa tells me all kinds of interesting stories he has heard about. He also asked me many questions. I am often moved by the comments that Minamigawa and the viewers make when they notice something. What interests me now is the process of how a person comes to be aware of something. With our recent work, I am really looking forward to seeing how the viewers will respond and how I myself will be affected by their responses.

Editor's thoughts......

The three members obviously trust each other, yet the decision to become a team could not have been an easy one considering that each member had originally been working as an artist. That is probably why they still need to hold the "mental meeting" twice a month. Now mé has already established itself as a unique art team, and continues to release works that evoke all kinds of emotions. In 2020, the team will float the image of somebody's face in the skies of Tokyo!(text_ikukohyodo)

RANKING

ALL

CATEGORY